2022 | Berlinale Shorts

Imagination Is Also an Answer

This year's selection of Berlinale Shorts is once again characterised by rich diversity. In addition to short features and animated films, the programme includes works of auto-fiction with CGI effects. In this interview, section head Anna Henckel-Donnersmarck explains what they all have in common: their dissatisfaction with merely addressing social ills. Instead, they use cinematic fantasy as a strategy in finding answers to the burning questions of our time.

Anastasia Arzhevikina and Ignat Dvoinikov in Trap

What do you find special about short film?

A short film has to know what it wants and use its limited time to the best effect. I like this focus and inner clarity. In addition, the genre enjoys great artistic freedom – which is why not only the chosen topics but also the formal and aesthetic approaches can be so different. A short film often works as a close-up of the bigger picture.

And a short film is rarely screened on its own since it is usually watched in a compilation programme. I’m intrigued by the resulting polyphony: What influence do the films have on each other? Do they enter into a dialogue or do they form more of an opposition? Does the programme flow smoothly or is it an emotional roller-coaster ride? Does every work have enough room to breathe? Curating a short film programme is like putting together a concert in which the various pieces of music should form a structure that works in and of itself.

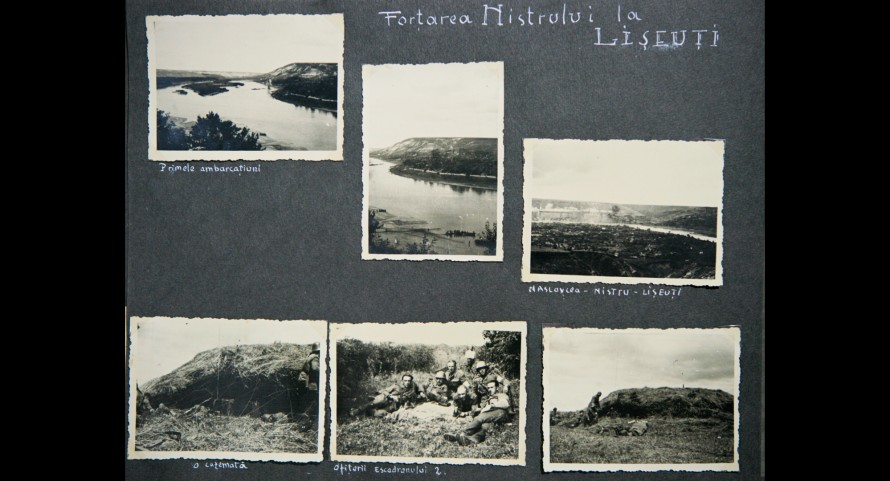

Amintiri de pe Frontul de Est

Taking a more detailed look at this “close-up of the bigger picture”, do you have any examples?

Amintiri de pe Frontul de Est (Memories from the Eastern Front) by Radu Jude and Adrian Cioflâncă is a good example. At first glance, not much seems to happen: we see an old photo album with handwritten captions being leafed through, and intertitles appear with quotations from historical documents. The film remains silent throughout its length of 30 minutes. The photos show everyday life during the campaign of the Romanian army’s 6th regiment in the war years of 1941 and 1942. With its formal minimalism, this work relies on the film to be continued in the viewer’s mind. It leaves enough space for us to recognise the larger context, to ponder further about what is being shown and to develop our own associations and feelings.

In Retreat , Anabela Angelovska takes a closer look at the construction sites in Kumanovo, North Macedonia’s second largest city. Since 2003, the US military has recruited workers there to work in the kitchens and laundries of its military bases in Afghanistan and Iraq. These young people earned very good money abroad with which their families back home could build their dream homes for them. With the retreat of the troops, many of them returned home, sometimes after years of deployment – and brought their war experiences and traumas with them. Just as in Amintiri de pe Frontul de Est, Angelovska’s film also illustrates the mechanisms of war. The economic effects, the extent of which I was previously unaware of, are shown here in all their complexity. At the same time, the film is a very interesting portrait of a family in which the grandmother becomes a real-estate entrepreneur, lending a hand herself on the building site while also herding the geese back into the barn.

In Agrilogistics we follow Gerard Ortín Castellví into a fully automated greenhouse. It is fascinating and frightening to see the effort with which nature is being industrialised. These huge mechanical gripping and shaking devices that sort tiny, delicate leaves – what a mind-boggling feat of engineering! But at the same time I think to myself: what arrogance! How far humanity has strayed from nature and how great is our desire to control everything. But then the film contrasts this reality with fantasy, re-empowering nature by letting her uncontrollably do as she pleases.

Haulout

Haulout by siblings Evgenia Arbugaeva and Maxim Arbugaev is a poignant lament on climate change. At first glance, it seems like a fiction film: a solitary man looks out to sea, speaks his observations into a dictaphone, carries out preparations and waits. One morning, they are suddenly there: the walruses. Like every year, they gather in this place. Gradually, we realise that there are far too many of them. And you wish it were actually a fiction film and not reality in which the animals are helplessly exposed to the manmade loss of their habitat.

Mo Harawe’s fiction film Will My Parents Come to See Me is equally harrowing: in calm, precisely composed images, a young male convict in Somalia is accompanied by a female guard through his last day before his execution. She knows the prescribed routine and silently fulfils her tasks. But, deep down, she can’t take all this anymore. Is it even possible to carry out a judicial killing in a humane manner? What does the death penalty do to the social environment in which it takes place?

Dirndlschuld

The very personal family stories, too, can be read as a depiction of society...

That’s true. In Dirndlschuld, Wilbirg Brainin-Donnenberg explores how narratives are continued and, to a certain extent, inherited – but also how they can be overwritten beyond recognition. She focuses on the traditional female costume of the dirndl and on the Grundlsee, a popular holiday destination in Austria. The film questions her own ambivalent relationship to them both: because behind the folklore and the picture postcard idyll, the deep-seated mindset shaped by National Socialism resurfaces time and again. It is sometimes glossed over, sometimes played down or covered up, but it is still present today.

In the fictional but autobiographically inspired Four Nights, Deepak Rauniyar shows the real life of filmmakers after the red carpet has been rolled up again. His film portrays a Nepalese couple – she, an actor; he, a director – who have to choose between idealism and pragmatism in their adopted country of the United States – because even in the land of opportunity, it is difficult to escape social designations.

In his poetic experimental film, Kicking the Clouds, Sky Hopinka also addresses the destructive power of designations by asking his mother about speaking and – above all – not speaking their own Indigenous language in his family. His great-grandmother was still forbidden to use the almost-forgotten Pechanga language. Ashamed of her origins, she began to deny them. His grandmother, on the other hand, is fighting to revive the supressed traditions, such as beadwork, which give her support and pride. The film is a very personal account of how hard it was – and still is – for Native American mothers to fight for a better place in society for themselves and their families.

Ana Vilaça in By Flávio

The motif of self-empowerment can be found in many of the films in Berlinale Shorts this year. For this, they venture into the unreal, almost magical with surprising frequency.

It’s actually interesting to see that the films are no longer content with merely chalking up social grievances. Instead, they choose cinematic fantasy as a strategy to find an answer to the urgent questions of our time. The works boldly upset the established power structures and liberate their protagonists from the usual character clichés.

For example, the stereotype of the single mother in Pedro Cabeleira’s By Flávio. The film’s starting point is a situation that’s often been told before: a mother has a date and doesn’t know what to do with her child. If such a woman follows her desire and has fun, she is usually punished for it, directly or indirectly. Not so in this film! It’s a joy to follow these characters and be repeatedly surprised by them.

Another interesting female character is Tomasa Ttito Condemayta who fought against the Spanish colonisers 250 years ago. However, Marina Herrera doesn’t tell us much about this Indigenous heroine in her film, Heroínas. Instead, she focuses on the women who venerate Tomasa like a saint today: they have dedicated a shrine to her skull, they make offerings, seek consolation and courage, dance and hold celebrations for her. Or are they just doing it for the camera? What is lived tradition, what is a mischievous re-enactment and where does staged fiction begin? It’s hard to say exactly, but maybe that’s not so important. Because Tomasa really existed, and even if the memorial to her isn’t real, the film at least has given her one – a memorial that can travel around the world and, like all good memorials, raises the curiosity in us to find out more.

Jai Rebière, Pauline Cormault and Inti Franc-Régis in Soum

In Soum, too, documentary observation is no longer distinguishable from fiction. Instead, it is heightened to the point of exaggeration for which the three protagonists have literally crafted their characters, and finds its climax in an absurd performance which is thrown in with great exuberance. At the same time, the conversations that the three protagonists have with their parents about their origins, spirituality and experiences of migration have an unadorned intimacy and sincerity that, in my opinion, can only be achieved in documentary. With this idiosyncratic mix of genres, Alice Brygo effectively expresses her generation’s “Lebensgefühl” (attitude towards life).

Almost like a companion piece to this, Trap captures snapshots of the lives of young adults in Russia: caught in the social grind, they seek the subversive power of ecstasy. Anastasia Veber intertwines the paths of her four characters in images of great physical presence and immediacy.

In a similar vein to Soum and Trap, the film Starfuckers decides at a certain point to leave the safety of realism behind. Two young actors take revenge on a director who has too often toyed with aspirations and abused his power. What they do best becomes their weapon: slipping from one role into the next. The film’s crowning glory is a disturbingly brilliant drag performance by Antonio Marziale, the film’s writer and director. I’m sure the tears at the film’s beginning and end are as real as they are artificial.

Polen Ly portrays a quiet process of emancipation in Chhngai Dach Alai (Further and Further Away). He gently depicts how two adult siblings deal with the loss of their home and the death of their parents. While the brother is drawn to the big city and towards a more promising, economically improved future, the sister wants to return to their submerged village because her parents’ souls have not yet come to rest. The protagonist is played by a member of the Indigenous Bunong people who live in north-eastern Cambodia and the film also had a mostly Indigenous crew behind the camera.

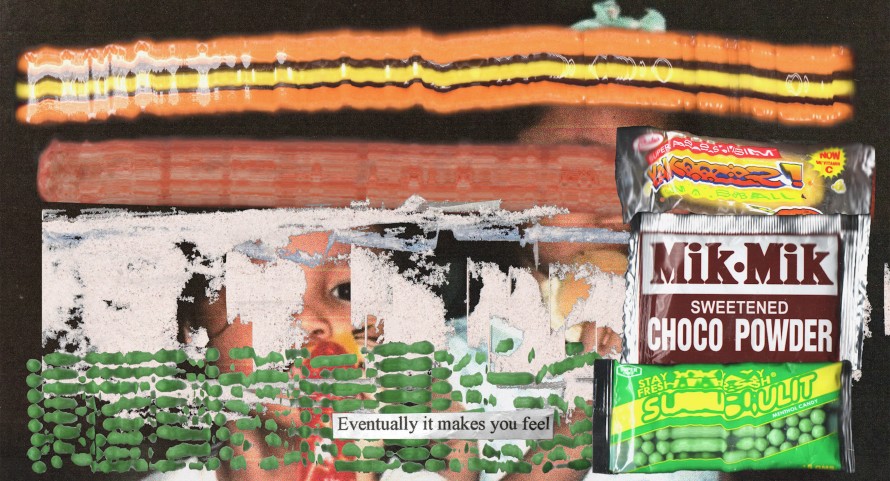

Ampangabagat Nin Talakba Ha Likol

In the introduction of the section in the programme booklet you mention the “radical subjectivity” of the filmmakers. What do you mean by this?

What I mean by this is the inner urge behind a film: Is there something that wants to express itself, that is searching for a way to the light? Or is the film eager to please me by fulfilling my expectations? Personally, I’m more interested in the first type of films and I’m happy when the filmmakers give me access to their world, even if I don’t understand everything I encounter there.

Maria Estela Paiso’s Ampangabagat Nin Talakba Ha Likol (It’s Raining Frogs Outside) is such a film. It is like a fever dream or an emotional outburst that is difficult to grasp. She herself says: “Solitude isn’t new to me. Even before all the dark forces of the world started having a party, I often consciously chose to be alone; however, when I no longer had the choice to be alone and was instead forced into solitude, my comfort zone gradually became uncomfortable.” The entire interview can be found on the Berlinale Shorts blog.

Jon-Jae-Ui Jib (House of Existence) is a pencil-drawn state of mind, a miniature perhaps best described by the word “melancholy”. After Math Test and Love Games, this is the third and, once again, very touching work by Joung Yumi at the Berlinale.

Bird in the Peninsula

Atsushi Wada’s work has also previously been presented at the Berlinale: his animation Gurehto Rabitto won a Silver Bear in 2012. In Bird in the Peninsula, he again plays with figures and symbols that pose riddles even to the young heroes of his story. They still have one foot in the magical world of childhood but are already practicing the discipline of approaching adulthood with the other, guided by their teacher.

Histoire pour 2 Trompettes is a dance, a vivid explosion of symbols, references and metamorphoses so fast, playful and charming that you can’t keep up and want to watch this magical animation again straight away. It is Amandine Meyer’s first film. In it, she traces her personal development towards being a woman, mother and artist.

Raquel Paixão in Manhã de Domingo

Manhã de Domingo (Sunday Morning) also depicts the path of an artist. In this case, a pianist gradually goes back into her childhood. The encounters she has in the film feel like placeholders for something she herself experienced long ago. The distinction between the present, memory and dream dissolves. It is also fascinating to follow her piano playing: she performs the same piece several times, but it sounds different each time, depending on whom she is playing for. In these moments, filmed with a discreet camera and without any cuts, the music has a peculiar immediacy that feels almost more intense than at a live concert. At least, that’s the effect it had on me.

El sembrador de estrellas (The Sower of Stars) by Lois Patiño is an enchanting and wistful ode to the nocturnal sparkles of the big city and the endless expanse of the starry sky. The sound carries us imperceptibly from one emotional world to the next, while magical spaces open up in the dark of the night.

Mars Exalté by Jean-Sébastian Chauvin is a poem that is difficult to put into words. I only want to say this much: the film is like a gift because it depicts sex as a tender secret. It was the first film we selected for the 2022 Berlinale Shorts.

Can you tell us more about your selection process?

Sure. Every film submitted to us is viewed by at least two people and is then either rejected or passed on to the committee which consists of the same people who make the pre-selection. This year they were (in alphabetical order): Wilhelm Faber (festival coordinator), Azin Feizabadi (filmmaker and visual artist), Alejo Franzetti (filmmaker), Maria Morata (film theorist and curator), Jana Riemann (programmer and film scholar), Sarah Schlüssel (programmer and cultural worker), Nihan Sivridag (cultural worker), Simone Späni (producer and cultural worker) and me (filmmaker and video artist). We view and discuss the films together and ultimately, as the head of the section, I decide – in consultation with our Artistic Director, Carlo Chatrian – which films are included in the programme.

And whom have you invited to serve on the Berlinale’s International Short Film Jury this year?

Payal Kapadia is familiar with Berlinale Shorts because her short film And What Is the Summer Saying premiered here in 2018. Her feature debut A Night of Knowing Nothing is a beautiful, magical film situated somewhere between documentary and fiction. It is very personal but also very political and it deeply moved me. What fascinates me most about Rosa Barba are her expansive installations in which she uses analogue film not only as a narrative medium but also as a tangible material: she creates magnificent kinetic sculptures from celluloid film strips, film spools, looping devices, projection machinery and other objects. Reinhard W. Wolf, on the other hand, not only has a keen eye but also an incredibly extensive knowledge about the past and present of short film as well as video art.

Cole Doman and Antonio Marziale in Starfuckers

Where can we find out more about the films in the 2022 Berlinale Shorts?

For “Berlinale Meets: Berlinale Shorts” we talked to the main actors in Four Nights, Starfuckers and By Flávio about being an actor in front of and behind the camera – since they also worked on their respective films as co-authors, producers or directors. We held another conversation with the cinematographers of Haulout, Agrilogistics and Will My Parents Come to See Me about the art of cinematography. And as part of Berlinale Talents, we are talking to the editors of Amintiri de pe Frontul de Est, Mars Exalté and The Sower of Stars about celebrating stillness and how to find the right rhythm in editing. All these talks can be found on the Berlinale website.

And once again this year, the Berlinale Shorts blog will feature texts on the selected films and interviews with the directors.