2022 | Forum Expanded

Closer to the Ground

2022 marks the first year for Forum Expanded without its founders Stefanie Schulte Strathaus and Anselm Franke who left the section in the summer. Ulrich Ziemons and Ala Younis have now assumed responsibility. In this interview, they discuss a special feeling that emerged during the viewing process, how the pandemic has changed the way we look at things and the zombie-esque aspects of “sustainable” nuclear energy.

Instant Life by Anja Dornieden, Juan David González Monroy and Andrew Kim

How does the first year without Stefanie and Anselm feel?

Ulrich Ziemons: Lonely (smiles). It’s interesting for me personally, because I have been with Forum Expanded for quite a while, but my role within the structure of the section changed. I have more responsibility, but the day-to-day work is basically alike. I'm taking care of the same processes as in the past years. What did change is the work on the programme because we have an almost completely new team. Dynamics in the group have altered with new people bringing in their interests and views. The way we organise our discussions in the selection process has changed, too, because the committee is spread out over different countries and time zones. We met mostly online, which worked out well.

Working remotely across countries sounds quite different than the 2022 Forum Expanded topic: Closer to the Ground. Is it related to these experiences?

UZ: Actually it is about this whole thinking about where one is situated. A lot of the films tell us about a specific locality and they try to dive into it. They are grounded in a particular situation and make us survey that situation and locality in a very detailed way, looking closer to discover different things than one might see when looking straight ahead or into the far distance. When we thought about the connection between the films we saw, we gravitated towards that idea of “Closer to the Ground”. It resonated with all of us, because we were thinking so much about where we were while meeting in a kind of dislocated way. There was a desire to feel gravity and being connected to the ground.

Jole Dobe Na (Those Who Do Not Drown) by Naeem Mohaiemen

What were the biggest challenges in the last year still dominated by Covid? Spotting new films usually requires a lot of traveling - could you travel a lot?

Ala Younis: We could travel, but with limitations. In terms of research we combined trips with our access to works through either Forum Expanded or the other projects we are involved in. We activated a lot of our contacts and advisors in different parts of the world. When we were finalising the programme, it was a funny situation because the conditions changed all the time. One day we could meet all together in-person, except one who had to be on Zoom. The next day it might be someone else on Zoom, always depending on the different Covid alerts we got on our phones. So there was, beyond overseas travels, the limitation regarding travels within the same city – questions of who may go to the office and who had to stay at home.

2022 is the second Covid year for the Berlinale. How has your and the artists' view changed under the impression of the pandemic?

AY: We definitely see now how Covid overshadows topics or images because of the situation we're in. The works that are produced right now, or the films that we can see now, are the results of a few months or years of work. Sometimes the project started just before the pandemic spread and the artists were interrupted due to the changing conditions. Many of the works might carry direct relationships to the times and circumstances, but not necessarily everything that could be done about the pandemic years is already produced. It is still processing in the minds of many of us.

vs by Lydia Nsiah

Regarding the widespread international curation team: Does the perspective on certain works change depending on the country you are watching it in?

UZ: I was in Berlin during the selection process, but in different localities. And even there it made a difference. A difference in terms of experiencing something together in a cinema, seeing a decently sized image; or sitting at home alone and watching it on a smaller screen. In this case, you have to perform distinct levels of extrapolation: imagining it in a cinema, imagine to watch it with a responding crowd. How will it relate to other films that we're choosing? Last year we already weren’t able to meet a lot, but this year there were new aspects of this divide.

Our colleague Shai Heredia lives in Bangalore, India, so because of the time difference most of the time it was evening for her when we met. And that changes the dynamic of seeing a film. You might get tired... and somebody else is watching the film in their morning, just after the first cup of coffee, you know? But I think that we were still able to create a concentrated space, detached from everything else, as in a cinema, when watching the films together. The conditions were not optimal, so we had to imagine optimal conditions. A lot of the films we are now showing will be part of programmes, interacting and conversing with each other.

Diva by Nicolas Cilins

With Diva by Nicolas Cilins you have a film in the programme that somehow benefits from the circumstances. How does it reflect the situation?

UZ: Diva is one of the works in the programme that reflects the way that interaction across geographies is still possible or could be imagined given the sort of travel restrictions we have. For Diva the filmmaker used footage that a Vietnamese social media personality is posting of herself online. Her name is Diva Cat Thy, she's a trans woman with a huge amount of followers in her homeland. She's a performer, but made her living selling noodles in a street stall during lockdown. Nicolas Cilins came across these videos not speaking Vietnamese. His partner Dustin Duong is Australian Vietnamese and knows the language to a certain extent. Dustin started translating for Nicolas. Their fascination for Diva led to the film, which is a kind of fan letter reflecting the relationship between the filmmaker and the translator, and the translator’s relationship to his parents' home country, Vietnam.

There are other films in the programme that do similar things. For example, If from Every Tongue It Drips by Sharlene Bamboata, a feature length film about a couple in Sri Lanka who is conversing with the filmmaker through Zoom and Skype. Like Diva, the film is about modes of translation - not just across languages, but also across geographies and social spheres. These are two examples where the pandemic is inscribed in the production process, but not overtly visible in the images. In other films, the pandemic appears as an allusion, for example through the topics of grief and loss, which were pretty prevalent this year.

One Big Bag by Every Ocean Hughes

Against the backdrop of the pandemic, One Big Bag by Every Ocean Hughes seems particularly interesting because although death has been omnipresent in the news over the last two years, the visibility of this multitude of deaths has mostly been limited to statistical representation…

AZ: One Big Bag is a formally straightforward film. It shows a death doula, a person who is taking care of dead bodies, preparing them for the funeral. She presents her bag of tools, most of them are everyday objects, and describes what particular object she will use for what and how you can make a dead body look a little bit more alive for the death watch. It's a very intense and simultaneously very factual way of speaking about death. The specific quality of the film is that it really goes through the highly emotional process that follows death.

Another work that touches this topic is Jole Dobe Na (Those Who Do Not Drown) by Naeem Mohaiemen. It is set inside a deserted, empty hospital and is an imagination of ailing and dying - the last scene in a woman's life who refuses to take a medication against her fatal illness. Her husband recalls the last moments in her life. But the wife is only in his imagination, because she died already. And to return to the question of how the view of certain works has changed in the face of the pandemic: Jole Dobe Na was shot just before the pandemic. As the filmmaker started editing, the virus hit. Suddenly lots of people were living on their own, losing their loved ones, or were distanced from them. So the film started to take on new meanings although this was not part of the discourse when the project started, nor the intended goal of the filmmaker.

Devil`s Peak by Simon Liu

These films connect the collective to the personal. In your biography on berlinale.de, Ala, it says you “often seek […] instances where historical and political events collapse into personal ones”. What fascinates you about this connection and is Devil’s Peak by Simon Liu something like the perfect film for you?

AY: There are many films in the programme that are really very close to me, but yes, especially Devil’s Peak. Certain political events overshadow our social lives, there are things that are happening on the bigger level than our personal one. And these have their consequences, like poverty or defeat or happiness. On the one hand they are collective experiences, but on the other they are translated into personal stories, affecting people in a direct way. And I'm really interested in how these conditions of the many affect the singular person. In Devil’s Peak there are these massive moments of riots or protests across Hong Kong. The film pays attention to the different parties that are involved, the protestors, the government, the police, but also to the filmmaker Simon Liu himself and his surroundings. We see these moments of collective agitation, a street full of heads. But we understand that every person within this street has their own story, there's an individual reason why they are there and where they will be afterwards. In this sense the film is zooming in and out, though not in the image sense, not in the way we'll see in the image.

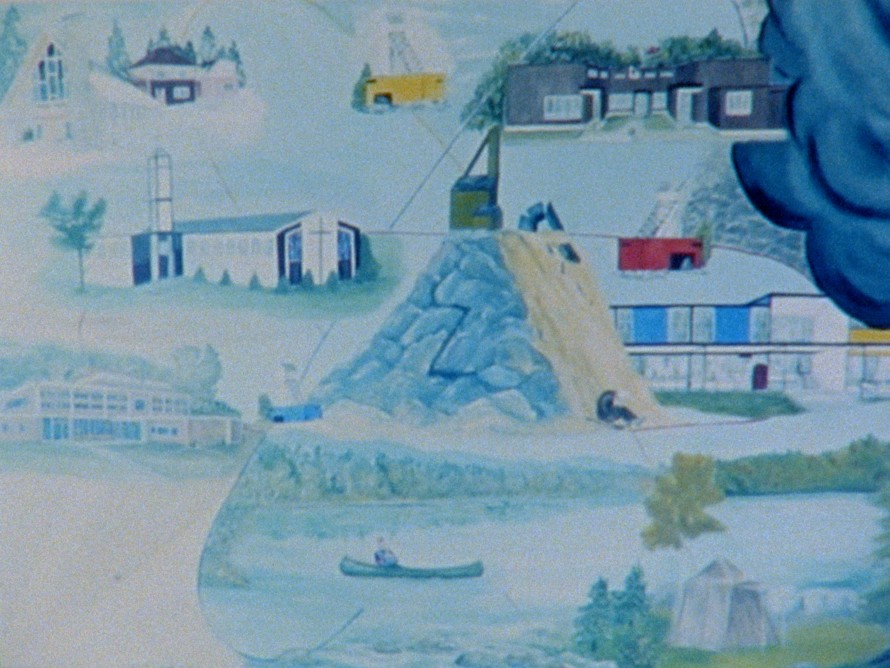

O dente do dragão (Dragon Tooth) by Rafael Castanheira Parrode

Apart from the pandemic, three works in the programme deal with a current topic regarding the discussions around sustainability in the EU. How does nuclear energy and its consequences appear in the works? There seems to be something ghostly about it?

UZ: Definitely. Radioactivity is a particularly interesting topic for a film - like everything which you cannot see - because it poses great challenges for a medium that deals with visual representation. The artists in the programme are dealing with this problem of making an invisible threat visible in different ways.

O dente do dragão (Dragon Tooth) by Rafael Castanheira Parrode looks at an incident that took place in the filmmaker's hometown of Goiânia, Brazil, in the late 1980s. A radiotherapy device was taken out of an abandoned hospital. People that dealt in scrap metal took it apart and found the radioactive substance locked away inside. They didn’t know what it was, but were fascinated - it had a blue glow. They handled it with their bare hands, passed it around. The radioactivity started to slowly spread through the city and contaminated a lot of people, it's one of the biggest civil nuclear catastrophes in history. The film uses a lot of found footage, so there are symbolic representations of a threat, like monsters, dragons, Godzilla. The film creates an atmosphere or a sense of what it feels like to be in this state of emergency.

Sonne Unter Tage (Sun Under Ground) by Alex Gerbaulet and Mareike Bernien shows a part of German nuclear history, namely the SAG Wismut, a Russian company that was extracting Uranium in Saxony, in the former GDR, and provided it for the nuclear power and weapons programme of the UDSSR. The film searches for traces of this history in the region, in which radiation can still be detected to this day.

Surface Rites by Parastoo Anoushahpour, Faraz Anoushahpour and Ryan Ferko

Sonne Unter Tage also uses found footage, archival material, unfolding the discourse around this material. How has it shaped the area, the political circumstances? How was it perceived on both sides of the German-German border?

UZ: It’s an essay film about the visible effects of this invisible substance, like, for example, glow in the dark objects around which a whole industry evolved.

Surface Rites by Parastoo Anoushahpour, Faraz Anoushahpour and Ryan Ferko, that also touches Uranium exploitation, does it in yet another way. Nuclear power is not at the centre of the film. It’s about a suburban area outside Toronto, Canada, that was also shaped by the nuclear power industry and weapon industry. The Uranium exploitation contaminated the area, which is adjacent to the land of the Serpent River First Nation. The area appears ghostlike, in a sense. Local teenagers made a zombie film there, visualising this idea of an undying entity coming to haunt that space. Which can stand for Uranium, but the film also deals with migration, the question of land rights, settler-colonialism and Indigenous rights in Canada. It is looking at all these political power relations that manifest in that space. And it has an eye for the weirdness of that place too – suburbia as a breeding ground for strange preoccupations of people.