2023 | Berlinale Shorts

Real-Life Fictions

Once again, the programme for Berlinale Shorts offers a deep dive into the broad spectrum and special creative freedom to be found in the short form. In this interview, section head Anna Henckel-Donnersmarck talks about how the films of the selection interweave the past and the present and place fiction and reality in relation to one another, as well as revealing which familiar names will be making a return to Berlinale Shorts this year.

Fatime Coulibaly in 8 by Anaïs-Tohé Commaret

Your enthusiasm for short film is rooted above all in the creative freedom that characterises the form. Which film from this year's selection represents this sort of freedom for you?

The film that comes to mind first is 8 by Anaïs-Tohé Commaret. A film that is incredibly difficult to grasp in words, that slips through your fingers as soon as you try to grab it. It drift, as if caught in the infinite curves of an 8, and does whatever it wants.

Other films forego a conventional narrative structure too, and are the expression of a feeling or mood. From Fish to Moon by Kevin Contento, for instance, or Qin mi (Daughter and Son) by Cheng Yu. I like how the people relate to one another in both films. There’s not a lot of action, but what does happen resonates for a long time and you leave the cinema with a feeling of comfort.

For me, however, artistic freedom also includes giving one’s self permission to tell a story in a conventional way. Everyone should choose the means that best do justice to that which is seeking expression. Anything is possible, nothing is mandatory. I am very grateful that we have the fantastic possibility at the Berlinale to share liberties artists take, when it comes to both form and content , with an audience that is eager to engage with them. And that we are able to operate in a society in which these liberties are established and protected by law

“Fiction Against a Real-Life Backdrop” is the theme of this year’s program. Did this motto play a role as you went about the pre-selection?

No, we watch all the submitted films without any preconceived concept. The patterns, connections and guiding thread first emerge when we have the final selection in front of us and we start to construct the programme. This year, the films are very heterogenous thematically. I find that parallels can rather be found in their narrative strategies. What is especially striking in this regard is the way reality and fiction are placed in relation to one another.

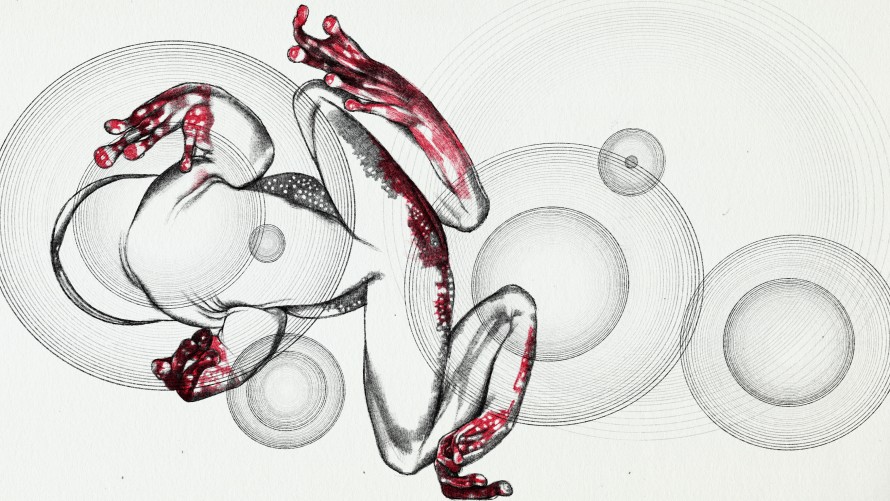

The Waiting by Volker Schlecht

Let’s take a closer look at these various strategies. Does the programme feature hybrid forms once again?

Yes, in several instances. The Waiting by Volker Schlecht is an animated documentary that provides a glimpse into everyday research practice in an unusual way. The departure point is an interview with a scientist specialising in frogs who is trying to understand their disappearance. Elegantly animated drawings illustrate what is said, occasionally becoming autonomous and meandering through their own world of associations.

An amplification of reality by artistic means also occurs in Terra Mater – Mother Land by Kantarama Gahigiri. This fierce poem places its afro-futuristic heroines on the endless piles of rubbish that are dumped in Africa and allows them to raise their voices, loud and proud, to denounce a global population that must finally take responsibility for the effects of colonialism, waste of resources, and environmental destruction.

Mwanamke Makueni (A Woman in Makueni) by Daria Belova and Valeri Aluskina

Mwanamke Makueni (A Woman in Makueni) by Daria Belova and Valeri Aluskina was also filmed on location – inside a prison and on the streets of Makueni in Kenya – and was created in collaboration with an amateur cast of locals. However, the fictional plot revolving around two lovers who are not permitted to be together could be set in any time or place.

Are there films which work with autobiographical elements?

Marungka tjalatjunu (Dipped in Black) by Matthew Thorne and Derik Lynch is based on the experiences of a man from the Anangu community. He also plays the main character and covers co-directing duties. The film is carried by his very calm yet proud presence and by the vast landscapes of Australia, immersed in golden light.

Ours (Bear) by Morgane Frund exposes the voyeuristic gaze of an amateur filmmaker. The film doesn’t get stuck in outrage though – instead it tackles the exhausting labour of confrontation and explanation and allows us to listen in on conversations between the female editor, who appears as the first-person narrator, and her client.

In Back by Yazan Rabee, a young man who fled to Europe from Syria describes his re-occurring nightmare. The film feels its way forward through the country's history, via a collage composed of news footage, feelings and fragmentary memories, in an attempt to get to the root of a trauma affecting an entire society.

Masa Zaher in Les chenilles by Michelle Keserwany

Are there any other films that reflect on today by looking into the past?

Les chenilles by Michelle Keserwany interweaves fiction-film elements with digressions into the history of silk production. The film takes the silkworms of the title as a departure point to connect Lyon with the Levante and the present with the past, thus opening up a conversation about exploitation, trauma and solidarity. At the same time, it paints a very beautiful portrait of a female friendship in exile.

In The Veiled City by Natalie Cubides-Brady , a time traveller from the future sets off for 1952 London, which is in danger of suffocating in the Great Smog produced by factory chimneys. In letters to her sister, she attempts to understand how one of the first man-made environmental disasters could happen, as well as the far-reaching effects that it would go on to have. The images are entirely drawn from archival footage from the period, while the letters are – presumably – fictional.

The Veiled City is conspicuously not the only film where a fictional plot unfolds before the background of a concrete historical event.

Yes, that is striking this year. The last trip to the polls for the 2022 runoff election in France between Macron and Le Pen is at the beginning of the “white night” of Nuits blanches (Schlaflose Nächte) by Donatienne Berthereau, for instance. Solène, the main character, refuses any sort of commitment, increasingly losing her grip in the end – perhaps also a portrait of contemporary society.

Solène Salvat in Nuits blanches (Sleepless Nights) by Donatienne Berthereau

Wo de peng you (All Tomorrow’s Parties) by Zhang Dalei begins on the last day of the 1990 Asian Games in Beijing and ends with a cinema screening of François Truffaut’s classic film Les quatre cents coups (The 400 Blows), organised by the labour union. In so doing, the film also addresses the question of who is able to identify with what form of culture – the mega-sporting event on the one hand and the improvised film screening on the other. Both help to foster a sense of community, but they fulfil very different purposes.

It’s a Date by Nadia Parfan is set in the very recent past, although a recent past which has unfortunately already entered into the history books: Kyiv 2022, during the Russian armed invasion of Ukraine. It is a remake of Claude Lelouch's C’était un rendez-vous (It Was a Date) from 1976, shot on another location and featuring a slightly altered ending: instead of a heterosexual couple, two women embrace here – one of them wearing military camouflage.

In addition to Wo de peng you and It’s a Date, Jill, Uncredited by Anthony Ing also takes a look back into film history.

Jill, Uncredited is a compilation drawn from 50 years of film and television history and an homage to the background actor Jill Goldston, who appeared in 2000 films. For me, it is just as much an homage to all the supporting actors in our everyday lives, to the people that aren’t in the spotlight, without whom our society would however collapse.

La herida luminosa (Daydreaming So Vividly About Our Spanish Holidays) by Christian Avilés

And then there are on the other hand films that act as artistic answers to societal developments and phenomena.

For more than ten years, “balconing” incidents have been on the rise in Spain’s tourist regions: young individuals, primarily male and often from Great Britain, attempt to jump into pools from the balconies of their hotels, injuring themselves seriously in the process, or even dying. The Spanish fiction film La herida luminosa (Daydreaming So Vividly About Our Spanish Holidays) by Christian Avilés gets inside the emotional world of British teenagers, exaggerating this phenomenon ad absurdum and attempting to name its root causes.

A Kind of Testament by Stephen Vuillemin is a very cool animated film drenched in saturated beauty that claims to be found footage from the Internet. The plot plays out on multiple levels and repeatedly throws unexpected, abrupt curves. It revolves around identity theft, fashion, cancer and death.

In many countries, the right to an abortion is under threat, increasingly forcing individuals to turn to the clandestine use of abortion pills . “I'll give you the beads, so you can make yourself a necklace” has been circulating as a corresponding code in self-help groups. The brilliantly written and acted fiction film As miçangas (The Beads) by Rafaela Camelo and Emanuel Lavorwas created as a reaction to this development.

As miçangas (Pearls) by Rafaela Camelo and Emanuel Lavor

There are quite a few directorial duos this year.

The previously mentioned Marungka tjalatjunu is the first co-directorial effort of Matthew Thorne, a white Australian, and Derik Lynch, a man with indigenous roots, who plays himself in the film. Les chenilles was directed by sisters Michelle and Noel Keserwany, whereby Michelle also wrote the screenplay and Noel plays one of the two main roles. Until now, the two have primarily appeared in a fine art context and as musicians, this is their first film. Mwanamke Makueni is the first collaboration between Daria Belova and Valeri Aluskina and was created in a workshop with Kenyan film students. Rafaela Camelo and Emanuel Lavor also co-directed together for the first time with As miçangas. By contrast, Eeva is Lucija Mrzljak and Morten Tšinakov’s third joint collaboration as directors. Their comedic, surreal yet sad animation film about the brutal end of a relationship was inspired by a dream Morten had, in which a woodpecker hammers a message in a coffin lid as morse code, before being beaten to death with an umbrella.

Eeva by Lucija Mrzljak and Morten Tšinakov

Are there filmmakers in this year’s selection whose work has already been featured at the Berlinale?

Billy Roisz is back and presenting once again, with Happy Doom, an abstract experimental film that makes the screen and loudspeakers pulsate and takes us along to experience a short, psychedelic rush of colour. Volker Schlecht and Alexander Lahl, the makers of The Waiting alongside Max Mönch, were our guests in 2016 with Kaputt (Broken – The Women’s Prison at Hoheneck). And Zhang Dalei, who won the Silver Bear at Berlinale Shorts in 2021 with Xia wu guo qu le yi ban (Day Is Done), is presenting not only the short film Wo de peng you this year, but also the series Why Try to Change Me Now. As far as I can recall, this is the very first multiple appearance of its type.

Who were you able to recruit this year for the International Jury of Berlinale Shorts?

The feature-film director Isabelle Stever is one of the most exciting voices in German cinema. She caused a stir at the Berlinale last year with Grand Jeté, which ran in Panorama. Cătălin Cristuțiu is an editor responsible for the montage of numerous Berlinale Bear winners, both short and feature-length films. He knows the Berlinale Shorts section well, as he was our guest in 2022 with Amintiri de pe Frontul de Est (Memories from the Eastern Front) and in 2019 with Blue Boy. Sky Hopinka is an artist working with film, photography, text and spatial installation. We showed his film Kicking the Clouds in 2022. Some of his current works are on display at Berlin’s Tanya Leighton Gallery until the end of February.

As section head, you are responsible for selecting the films. Who supports you in this process, and what expertise and experience do these individuals bring with them?

Theory and practice are equally represented on our team: the committee consists of filmmakers, film scholars, curators, artists and cultural workers. We grew up in Argentina, Germany, Indonesia, Japan, Spain, Switzerland and Ukraine, and lived and worked later in Barcelona, Berlin, Bologna, Duhok, Kigali, London, Mexico City, New York City, Paris, Ramallah and/or Tehran. Some of us have been involved since the founding of the section in 2007, others joined the team two years ago. The members are, in alphabetical order: Wilhelm Faber, Azin Feizabadi, Alejo Franzetti, Maria Morata, Jana Riemann, Sarah Schlüssel, Nihan Sivridag and Simone Späni.

Where can we learn more about the films?

The short film talks, which we conduct with the film team in the cinema following the screening of their film, are one possibility. At the repeat screenings known as Shorts Take Their Time (STTT) we take the time to enter into more extensive discussion and invite the audience to join. I find it just as exciting to re-live a film through the eyes of another person, which is why I am really looking forward to the sketches of the artist Dorothea Schulz, who, seated in the dark cinema, will once again be capturing her impressions of films through drawing. These sketches will be available on the Berlinale Shorts blog, and the same goes for the press reviews of the individual films and interviews with all of our filmmakers, which will be updated and expanded on a regular basis.