2024 | Panorama

Bridges to the Possible

The 2024 Panorama once again has its fingers on the pulse of the zeitgeist. In this interview, section head Michael Stütz talks about how the films consistently succeed in building bridges across the fault lines of our times into a possible future, about exceptional life stories and the enormous formal diversity in the programme.

Mzia Arabuli in Crossing by Levan Akin

In the press release, you summarise the programme with the title “Bridges Between Lived Experiences and Cinematic Possibilities”. What exactly do you mean by that?

MS: For me, many of the films in the programme succeed in building these bridges by exploring the gaps between experienced reality and cinematic possibilities – especially in light of the political dead ends we’re constantly heading into at the moment, both as a society and as individuals. In this sense, regardless of whether they’re approaching their subject matters in a fictional, documentary, aesthetics-based or pared back way, the films develop a counter-proposal as a possibility for the audience. Based on a reality that could well have a traumatic context which we might want to turn away from, but which we ultimately have to face, the films create alternatives. They present ways in which we as a society and as individuals can retell stories to begin a healing process or simply to take the next step in order to stop us from giving up and to be able to think positively about the future.

Can you give a specific example?

Our opening film, Crossing by Levan Akin, explores all sides of this aspect. There’s a very strong concept behind the film, it doesn’t want to present itself as realistic. But, at the same time, it deliberately shows the audience that there are different ways to tell queer stories. It presents one way – and that could perhaps be the reality. But there are other possibilities that are not only suggested in Crossing, but are actually shown. And then the viewer can decide which path they want to go down and in which direction they want to think. By opening up these alternate realities, Levan Akin presents us with a moment of self-determination that counteracts social repression. He makes a proposition that doesn’t necessarily correspond to reality, but that we can adopt.

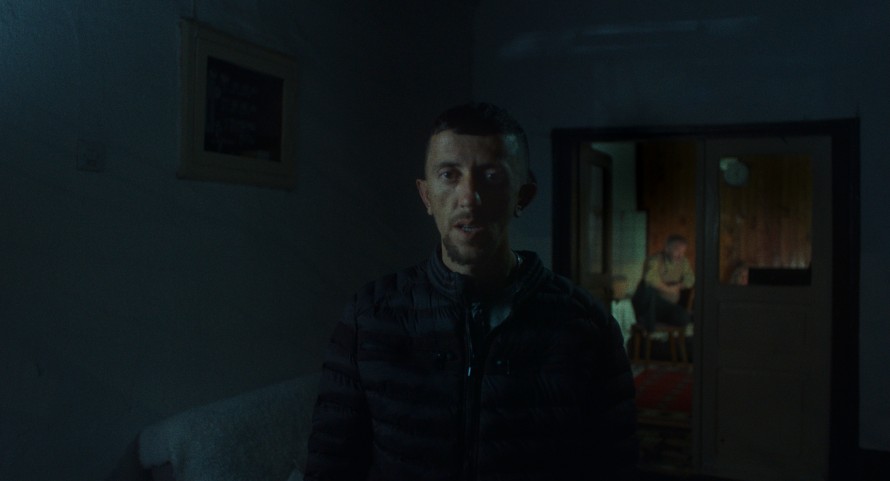

Gëzim Kelmendi in Afterwar by Birgitte Stærmose

Images of War

One of the most significant films in relation to our current war-torn global political situation would appear to be Afterwar, which deals with the trauma left behind by the now almost forgotten war in Kosovo. How does the film approach the devastation of violence?

The production takes a highly aesthetics-based approach, not only on the visual level but particularly with the sound. Afterwar is a hybrid film that I first saw on a selection trip in Copenhagen. We then entered into a dialogue with the filmmakers to find out how the material, which was shot over 15 years, and this very special form of production came about. The people in front of the camera, who wish to be called actors and not protagonists, were very closely involved in the development of the work, including in the writing of the script and the drafting of dramatic ideas. They didn’t want a traditional interview format. They are rightly listed as co-creators in the credits. We felt it was important to understand this collective, egalitarian creative process.

Was working on the film a kind of healing process for the actors?

There was constantly an intensive exchange and the need to bring these staged scenes to the screen to gain a certain amount of self-determination and distance from their own past, but without falsifying the truth. Afterwar makes it very clear that there are no winners in war. The Kosovo War was 25 years ago, but that’s the blink of an eye when you see the trauma it inflicted.

Basel Adra and Yuval Abraham in No Other Land by Basel Adra, Hamdan Ballal, Yuval Abraham and Rachel Szor

The Hamas attack on Israel on October 7, 2023 and the war that has been raging in the region ever since have created a heated, completely polarised atmosphere full of hostility on both sides, including in Germany. With No Other Land by Basel Adra, Hamdan Ballal, Yuval Abrahamund and Rachel Szor, you are screening a film from the region that deals specifically with Israeli settlement policy. How did you find the courage to include this film in the programme?

I would have shown the film in any other year, that was the decisive factor for me. It would have been wrong not to invite the film due to the current political tensions. On top of that, Panorama has a strong tradition of presenting films from Palestine and Israel.

The film is founded on the friendship between a Palestinian activist and an Israeli journalist. Would you have shown the film if it hadn’t have emerged out of this Palestinian-Israeli collective?

The process of mediation via this friendship is an extremely important aspect of the film. But just as important is the political alliance between Basel and Yuval in their fight and their peaceful activism. They critically raise their voices against Israel’s settlement policy and the displacement of communities. And the undeniable inequalities between the two of them are constantly reflected upon, too. These disparities are so significant because they ask how anyone could even countenance the idea of not granting someone else the most basic human rights. The film offers a lot of material for discussion, but also the potential to lead a peaceful and future-oriented discourse. At Panorama, we want to be in the position to offer this platform, just as we have done in the past. That’s why it’s important to show No Other Land this year. And we’re delighted that all four directors are coming to Berlin.

A Bit of a Stranger by Svitlana Lishchynska

A Bit of a Stranger sheds light on another violence-filled relationship between two states...

The film is a very intimate reflection and processing of a trauma that is still new and growing: the one caused by the Russian war of aggression on Ukraine. It tells the story of three generations of women in one family. The director Svitlana Lishchynska represents the middle generation: she was born in the late 1960s, her mother in the late 1940s and her daughter in the early 1990s. What is surprising is that it was easiest for the older generation, that of the mother, to let go of the Russian identity that had shaped her for a long time as a result of Russian imperialism and the colonisation of Ukraine. The younger the generation, the more difficult this process became – because Russification had been passed down on a linguistic and cultural level for decades. Thus, the director’s daughter takes the longest to develop a critical consciousness. Only when the war of aggression begins does she slowly start to change her perspective. When the daughter leaves Ukraine for London, she can no longer escape the trauma. Even in a safe country, the mind and body are still preoccupied with the conflict. War is often told from a very male point of view. That’s why I find it all the more important for us to be able to show a decidedly female and cross-generational perspective this year.

Jürgen Baldiga in Baldiga – Entsichertes Herz (Baldiga – Unlocked Heart) by Markus Stein

Life Stories

Baldiga – Entsichertes Herz (Baldiga – Unlocked Heart) by Markus Stein offers a deep insight into the queer subculture of West Berlin in the 1980s. What was it like for you to experience this dive into the past?

I was really looking forward to this film because Jürgen Baldiga hadn’t exactly been unknown to me, but his life and legacy hadn’t really sunk in before. His estate had a wealth of photographs and diary entries that had not yet been fully appraised. That’s exactly what Markus Stein’s film does now in a really impressive way. It is about a time that I didn’t experience myself, but which has always held a strong fascination for my generation. Baldiga is a great trip back in time featuring a large number of well-known protagonists who made history in West Berlin. The film celebrates their memories and at the same time enables us to experience the joy of life of that period: the sexual freedom and the tearing down of so many social boundaries. Baldiga led a thoroughly political life shaped by the understanding of his own body, his self-determination and his sexuality. He reminds my generation and the many even younger generations who will hopefully watch the film that many people came before us and we are now standing on their shoulders. This look back into the past is important to enable us to understand the present and to imagine a possible future. Another major topic of the film is AIDS because, after he was infected, Baldiga became a deeply fearless chronicler of the disease and of his own approaching death. I have rarely seen such an honesty as he displays which makes his everyday life so directly tangible. The picture that emerges is of a journey, a development. And a record of the people around Baldiga, his queer adopted family, their solidarity and support.

Libuše Jarcovjáková in Ještě nejsem, kým chci být (I’m Not Everything I Want to Be) by Klára Tasovská

Another photographer, Libuše Jarcovjáková, who is portrayed in Klára Tasovská’s film Ještě nejsem, kým chci být (I’m Not Everything I Want to Be), was working in West Berlin at almost the same time. It might not be too far-fetched to assume that she and Baldiga met at some point...

True, yes, they really could have met in the 1980s. Of course, Ještě nejsem, kým chci být and Baldiga complement each other really well. Although the former is genuinely told 100 percent via the photographs from Libuše Jarcovjáková’s archive. It covers the period from around 1968 to the early 1990s during which she takes us on her life’s journey from Prague via Tokyo back to Prague and then Berlin. In a voiceover, she reads out her own diary entries which gives the film a particularly personal touch. It portrays an identity that never comes to rest, that is never fully grown up nor fully formed. Her story begins immediately after the suppression of the Prague Spring and the associated restrictive, repressive effects on a society that had hoped to be able to live more freely. Jarcovjáková is working in a factory at that time, documenting her days with the workers whom she is fascinated by. She is also part of the queer community, has a relationship with a woman and is experimenting with all sorts of things.

Sol Carballo in Memorias de un cuerpo que arde (Memories of a Burning Body) by Antonella Sudasassi Furniss

Another film about a liberation is Memorias de un cuerpo que arde (Memories of a Burning Body) by Antonella Sudasassi Furniss. And it’s further proof of the truly extraordinary variety of forms in this year’s programme, wouldn’t you agree?

The film certainly takes a really interesting structural approach. And yes, it also addresses – although not exclusively – sexuality and self-determination over one’s own body and desire. It also deals with the personal and social traumas that have become inscribed in the lives of the women it portrays: women who grew up in a culture shaped by the patriarchy and religion. We hear in voiceover the true life stories of three women who never appear onscreen while, at the same time, a fiction film about a woman unfolds in images which dramatise what the voiceovers are describing. You see this woman from childhood to the point when she is married off, forced to enter an unhappy relationship with a violent man. Today, the three protagonists are in their late 60s and early 70s and come across as totally undefeated, discovering a new joie de vivre in their third phase of life and celebrating a new self-determination and late-blooming sexuality. These women are a powerful expression of the feminist gaze: it is they themselves and not anybody else who is telling their stories.

As with Afterwar, the question again arises about who is telling which story and who gets to portray themselves?

Absolutely. There really is a huge range of different structural approaches in this year’s programme. In Sayyareye dozdide shodeye man (My Stolen Planet), Farahnaz Sharifi uses found footage to write her own biography and an alternative history of Iran from a female perspective that is not present in the public sphere in Iran. And this variety of forms means that the films are communicating very strongly with each other.

Saoirse Ronan in The Outrun by Nora Fingscheidt

Places of Refuge

In many films, the location is an important part of the narrative: the Spanish tourist hotspot of Benidorm in Les Paradis de Diane (Paradises of Diane) by Carmen Jaquier and Jan Gassmann; the rugged coast of Scotland in The Outrun by Nora Fingscheidt; Lençóis Maranhenses in the north of Brazil in Marcelo Botta’s Betânia; or the Colombian jungle in Yo vi tres luces negras (I Saw Three Black Lights). What are the relationships between these special places and the characters?

In The Outrun and Betânia, the locations are places of refuge or places of return: places where the characters deal with their traumas. Benidorm in Les paradis de Diane is different. The city holds no memories for the protagonist but instead offers her the opportunity to go completely undercover and disappear. This act is impressive in its radicalism. After the birth of her child, the protagonist catapults herself entirely out of her extremely middle-class and secure Swiss society by simply running away. But her body chases after her psyche and catches up with it again and again. The location makes the character’s detachment and loneliness stand out even more. The only person with whom Diane forms a connection is already fading away and existing only as a ghost. The Outrun depicts a return, a search for the self and a confrontation with the wounds of the past which the main character has partly inflicted on herself, but which also have their origins in her childhood. The film interweaves many different levels of time. Betânia and Yo vi tres luces negras by Santiago Lozano Álvarez are about dealing with grief. In Yo vi tres luces negras, it is also grief about one’s own death and the accompanying ritual, intertwined with a crime story full of bloody paramilitary battles. These two films are connected by their use of music: songs that are sung to enrich the stories. In Betânia, the location of Lençóis Maranhenses creates a compelling fascination. The lagoons and the salt and the constant motion are also a reflection of Brazilian society.