1968

18th Berlin International Film Festival

June 21 – July 2, 1968

“To blow up the festival would be a dubious victory for the students. It would be better to force another type of festival.” – Film critic Enno Patalas, ahead of the 1968 Berlinale in “Die Zeit“

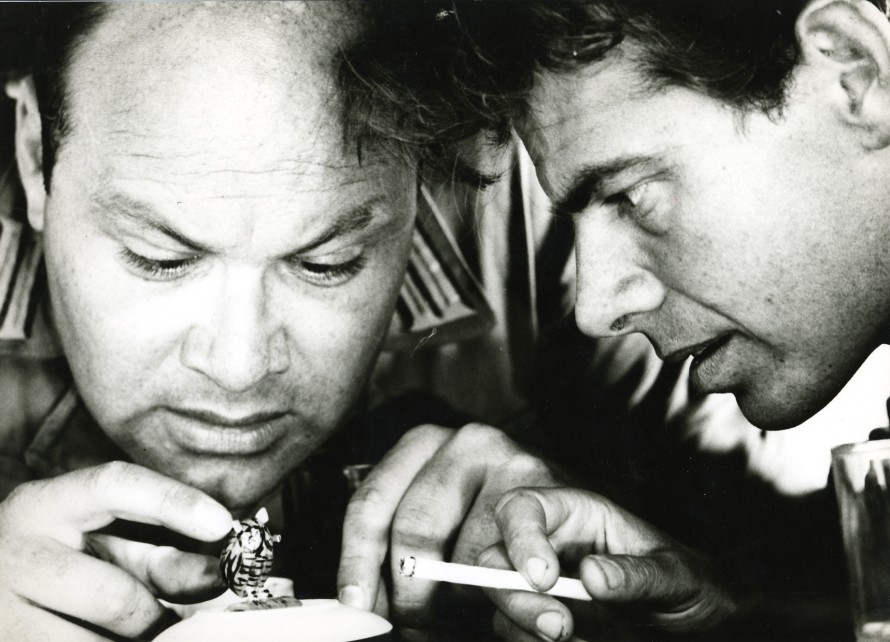

Wolfgang Reichmann and Peter Brogle in Lebenszeichen by Werner Herzog

"A la grande salle!"

Two years earlier, film critic Enno Patalas had demanded that the Berlinale distinguish itself from its model Cannes. Then, in Cannes happened this: protesting students and striking workers occupy the festival as a platform for agitation. Many filmmakers declare their solidarity and Jean-Luc Goddard calls for a type of storming of the Bastille, whereby this time cinema is the captive to be liberated: “A la grande salle!” Festival director Favre Le Bret breaks the festival off. The “unthinkable” has become reality.

In Berlin, preparations were underway for a similar situation. Preventative measures were discussed, which could prevent the break-up of the festival. It was clear that one had to acknowledge social developments and the student protest. Not everyone saw the tense situation as a danger. Enno Patalas saw here an opportunity for the Berlinale. For him the protests were in line with what he had previously called for, namely to make the Berlinale a “place of confrontation, not just mutual compliments”. He suggested not letting it come to victory or capitulation, but to open up the Berlinale to social protest – an idea that assumed the student’s willingness to cooperate.

Tauentzienstraße

The revolution didn't take place

But 1968 wasn’t so simple. There were more fronts than was initially apparent. At a discussion, which was supposed to sound out the possibilities for a “different festival”, Patalas, Alexander Kluge, Edgar Reitz, Christian Rischert and Johannes were egged. They had believed themselves to be on the side of the protesting students, but for them they were just “lackeys of the establishment”. So there was ample confrontation. And no compliments for anyone – Patalas had imagined it differently.

While the opposition fought with itself, the Berlinale was left relatively unchallenged. “The revolution didn’t take place,” wrote Wolfgang Jacobsen in “50 Years Berlinale” and regretted it: “The opportunity to influence the festival, to restructure the content, even the chances for a counter-festival were greater than ever.” The Senate and festival management were ready to react in order to save the Berlinale – in whatever form.

In a public event under the notably careful slogan “What Chances Does the Berlinale Have?” Alfred Bauer and the head of the Berliner Festspiele Walther Schmiederer opened themselves up to criticism. At the podium were also Enno Patalas and Ulrich Gregor. It wasn’t just about the festival, but also fundamental criticism of the film industry, means of distribution and films in general: distribution companies should be dispossessed and ticket prices abolished. Everything was put into question, everything seemed possible, though all that was actually realised at first was the establishment of “permanent public debates” and the screening of dffb (German Film and TV Academy Berlin) films in the framework of the Berlinale.

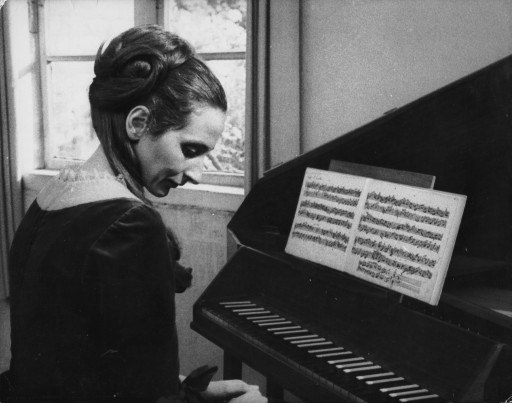

Christiane Lang-Drewanz in Chronik der Anna Magdalena Bach

A festival of its times

But beyond this, the festival bore the signs of the times: Godard’s Week-End was seen as the continuation of reality through the means of cinema and was the most striking film of the Competition. Jean-Marie Straub’s Chronik der Anna Magdalena Bach | The Chronicle of Anna Magdalena Bach connected in many ways to the fundamental criticism of society and its forms of reproduction: “This film is (also) a protest, even a strike against film support legislation and an appeal for societal and economic structures that make every film accessible,” wrote Straub in a letter to Bauer, in which he explained why, “despite everything”, he was showing his film at a festival.

What did Bauer think? He had made an effort to secure Roman Polanski’s Rosemary’s Baby and Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey for the Competition, but didn’t get them. He could have got the Beatles film Yellow Submarine but didn’t want it. To his credit at least, he did get and show Werner Herzog’s debut Lebenszeichen | Signs of Life.