1971

21st Berlin International Film Festival

June 26 – July 6, 1971

“The 20th International Berlin Film Festival of 1970 did not take place. What was supposed to be an anniversary year was a year zero. In a way, this is an opportunity – let’s wait and see how it gets squandered.” – Alfred Brustellin in the "Süddeutsche Zeitung" after the 1970 scandal.

It is Not the Homosexual Who Is Perverse, But the Society in Which He Lives

The "counter-festival" is integrated

The 1971 festival took place under the spell of the previous year’s scandal. Although many observers had predicted the end of the Berlinale, it nevertheless had been possible in a matter of a year to bring together the various factions – the “old” and the “new” – in a constructive dialogue. Not only that, but the critics themselves were invited to take on some of the responsibility for change: That year, the International Forum for New Cinema was launched as an official part of the Berlinale. The “Friends of the German Cinemateque” around Ulrich Gregor and Manfred Salzgeber were given their own modest budget to put together a programme reflecting their goals of renewal, openness and critical discourse. What had begun as an anti-festival now served to expand the horizons of the Berlinale. Many saw this step as the salvation of the festival, although certain anachronisms were also impossible to ignore. It was to take years before elements that did not – and did not want to – belong together would fuse into a whole.

The critic's responsibility

“To publicize and support progressive and avant-garde developments in film from around the world” was the declared goal of the creators of the Forum. Just as important as showing the films were the discussions following them and the promotion of a differentiated reception of what was shown on the screen. Informational material was provided to accompany the Forum films; there were also panel discussions and an overall effort to show the “commonalities and contradictions between the individual films”. There was a conscious choice not to award prizes, since “the attempt to create a hierarchy of quality or merit among films of diverse intentions and forms” seemed “fundamentally questionable” to the organizers.

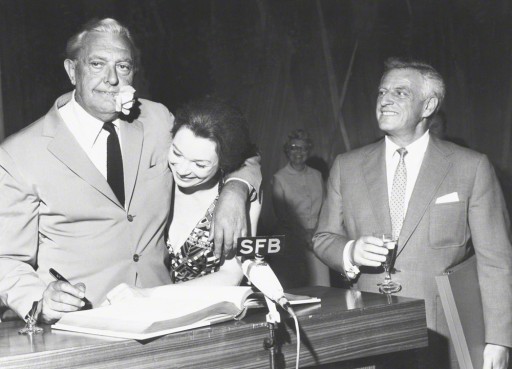

Jaques Tati, Shirley MacLaine, Stanley Kramer

Criticism of the way the festival had been structured so far was unmistakable in all of this. It was not only that the Berlinale, like all large film festivals, lived to a large degree off of the attention generated by the Competition. It was also no coincidence that the explicit appreciation of “contradictions” and “incomparability” sounded like a delayed answer to Alfred Bauer’s 1963 "Tagesspiegel" piece. He had described the festival as a “competitive exhibition” and referred to the "idealistic nature” of his own role as festival director, striking a noncommittal, pacifying note that seemed a vestige of the 1950s.

Bauer remains skeptical

Bauer’s basic position changed little in the course of the turbulent 1960s. No one was surprised, then, that he initially saw the International Forum for New Cinema primarily as a competitor and felt that the division of the festival was an unsatisfactory pseudo-solution. “All of the trends in cinema” were represented this year, he summed up, not without an indignant undertone, at the end of the festival, “art, commerce, documentary, ideology, and agitation”. These were buzz words of the times, and showed that the dispute, whether it was desired or not, was already taking place. Where there were conflicts and differences of opinion it was important to develop a robust culture of debate. And in order for this to happen, the conflicting positions had to first be articulated.

Der große Verhau by Alexander Kluge

The focus of the Forum programme was on new German films by Ula Stöckl, Edgar Reitz and Alexander Kluge, politically oriented features and documentaries, experimental cinema, and films from previously under-represented countries. With Rosa von Praunheim’s Nicht der Homosexuelle ist pervers, sondern die Situation in der er lebt | It is Not the Homosexual Who Is Perverse, But the Society in Which He Lives, aggressive target group cinema made its debut at the Berlinale. The extremely diverse programme seemed to want to make up for what had been neglected in the past, with a number of “modern classics” explicitly serving this purpose.

Immediate recognition for the Forum

The success of the Forum was generally interpreted as a confirmation of the long-standing criticism of the festival. “The important films have migrated to the side festival,” Friedrich Luft observed in "Die Welt". “The so-called relevant films won’t trouble the main festival any longer.” Polemics like this of course added fuel to the flames of the internal conflicts of the festival, and they also overshot their mark – after all, the Competition this year showed new films by Ingmar Bergman, Pier Paolo Pasolini, Vittorio de Sica, Rainer Werner Fassbinder, Robert Bresson and Kon Ichikawa. Indeed, now the baby had to be kept from being thrown out with the bathwater. In the long run, the festival’s concern had to be to combine the critical and disturbing potential of film with its broad appeal.