1991

41st Berlin International Film Festival

February 15 – 26, 1991

“The 41st International Film Festival is an act of faith, of courage, an attempt to overcome psychosis and to express interest in the other, whether he be American, English, Jew or Arab. We Germans also need to speak with each other, learn to understand each other”. – Moritz de Hadeln in the foreword to the festival catalogue, defending his decision to let the Berlinale take place despite – or precisely because of – the Gulf War.

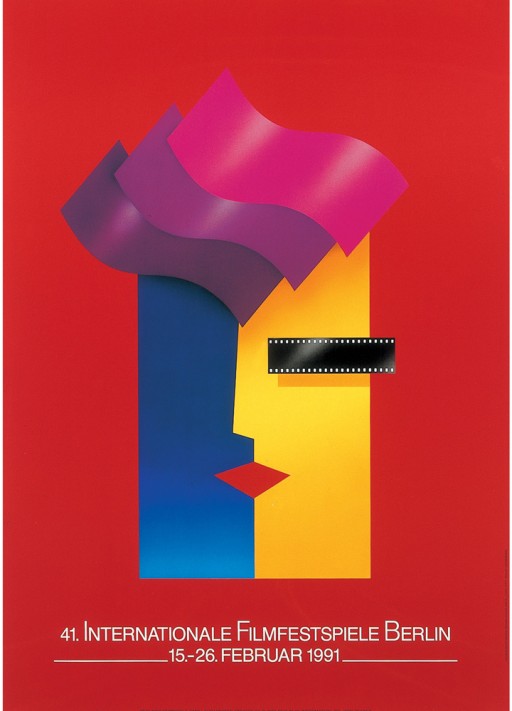

The poster of the 41st Berlinale

Now more than ever: no surrender in the war of images

On January 16, war broke out in the Gulf. Immediately there were speculations that the Berlinale would be cancelled. But what would have been gained by that? In a passionate foreword to the festival catalogue, Moritz de Hadeln defended his and Ulrich Gregor’s decision not to cancel the Berlinale. Angrily he castigated the West’s ignorance of Arab culture, the interpretive monopoly of American war reporting and its acceptance by the viewing public. Instead of a timid retreat into the private zone in front of the television and its “indoctrinating” message, he invoked the connecting power of dialogue the film festival sought to promote. “What to do? Our answer is simple: We want to do everything possible to devote this festival to international dialogue. This cannot happen hysterically or fearfully, it cannot happen if we stay at home to follow the latest reports from the Gulf.”

A strong presence of European films in the Competition this year was meant to counteract the supremacy of American movies. Moritz de Hadeln had been repeatedly accused of being too eager to show major US productions in the Competition. It was not, however, an outstanding year for European cinema. De Hadeln had sagely written in the festival catalogue: “In order to select, a selection has to be possible”, meaning only that film production in the Middle East, Africa and Latin America was still scanty. But by no means did the Berlinale always have first choice of even the prosperous European countries’ films. Competition with Cannes was by now as formidable a barrier as were the financial straits of the “Third World”.

Anthony Hopkins, who was a guest with The Silence Of The Lambs, and Jane Russell, to whom the Homage was dedicated

Wide discrepancies in the quality of European films

Neil Jordan’s The Miracle, Simon Callow’s The Ballad of the Sad Café and Viktor Aristov’s Satana | Satan were among the few European films that were able to convince both critics and audience. The two German Competition entries seemed to reflect the devastating effects of the new German film funding policy, as a result of which most feature films could only be made as TV co-productions. Franz Seitz’ Erfolg | Success and Roland Gräf’s Der Tangospieler | The Tango Player were not able to convince their audiences.

That three of four Italian entries were awarded with a main prize – La casa del sorriso | The House of Smiles by Marco Ferreri, La Ccondanna | The Condemnation by Marco Bellocchio and Ultra by Ricky Tognazzi – was seen as a misguided affirmation of what was but a merely well-meant effort. The jury had done European film a disservice – after all, it would not have been a disgrace to give Jonathan Demme the Best Director Silver Bear for The Silence of the Lambs or to honour a film like Cabeza de Vaca, the debut film by Mexican director Nicolas Echevarria. This at least was the gist of many of the commentaries following the awards ceremony.

Collectively overlooked by the media, the public and the jury was Pantelis Voulgari’s Isiches Meres tou Avgoustou | Quiet Days of August, a film whose gentle poetry cast a spell over the few who saw it. “Small”, intimate films threatened to go under in a Competition that again and again was perceived – and perhaps also overestimated – as a clash of cultures. Finnish director Aki Kaurismäki seemed to be well aware of this when he decreed that his films could be shown at the Berlinale, but never in the Competition. This year, his I Hired a Contract Killer provided the Forum with a veritable hit.

Presented The Godfather Part III: Francis Ford Coppola

Open borders – open competition

In the year one (and a half) after the fall of the Berlin wall there were high expectations of the Berlinale. Observers were eager to see whether the festival would succeed in maintaining its status as the most important festival for Eastern European cinema. It quickly became clear however that the opening of the borders had also led to stiffer competition between the festivals. Several interesting films from Eastern Europe were not even offered to the Berlinale or were withdrawn at short notice in favour of Cannes. So in the end Aristov’s Satana and the Slovakian entry Ked Hviezdy boli cervené by Dusan Trancíks were the only Eastern European films in the Competition.

On the other hand, Eastern European filmmaking continued to be strongly represented in the Forum and Panorama. The Hungarian satire Isten Hátrafelé Megy | God Walks Backwards by Miklós Jancsó in the Panorama, Alexandr Sokurov’s study on death Krug vtoroy | The Second Circle and Gluchy Telefon | Crossed Lines by Polish director Piotr Mikucki were exciting steps towards a new post-communist film language.

Film cultures – old and new

A retrospective of Romanian documentaries from 1898 to 1990, showing a remarkable continuity of totalitarian regimes, also received a lot of attention. “Even the silent films from the 1920s, mostly short features on the pomp and pageantry of the royals, seemed, in light of the cult of personality to come, like a prologue to the vain self-portrayals of the Ceaucescu clan”, Dieter Bertz wrote in the weekly “Freitag”.

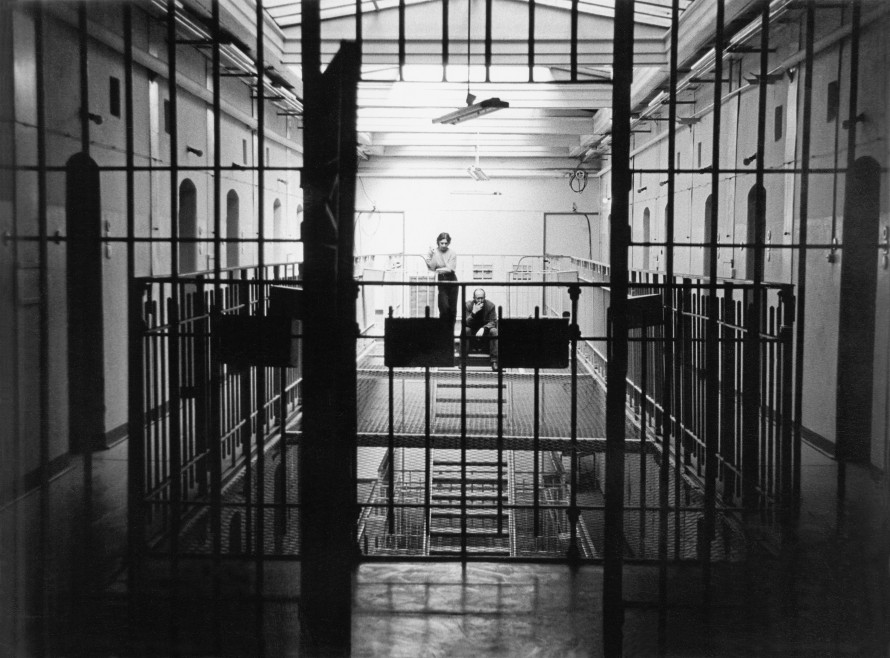

Verriegelte Zeit

Mexican cinema, which already made a good impression in the Competition with Nicholas Echevarria’s Cabeza de vaca, showed itself to be extremely lively in a special series in the Forum. The Berlinale audience was introduced to a cinematography it was to see more of in the future. The German films in the Forum were also persuasive, or at least their themes were on the pulse of their time. “Farewell ceremonies”, Klaus Dermutz wrote in the “Süddeutsche Zeitung”, referring to the conspicuously large number of German films (including East-West co-productions) that addressed the reunification and especially the uncertainty over the common future. Jürgen Böttcher’s Die Mauer, Andreas Voigt’s Letztes Jahr Titanic, Sibylle Schoenemann’s Verriegelte Zeit | Locked-Up Time, Ulrike Ottinger’s Countdown and Ein schmales Stück Deutschland by Lew Hohlmann, Joachim Tschirner and Klaus Salge all shared this thematic preoccupation.

In addition to a festival that could best be described as mixed – and disappointing after such high expectations – there was also the sobering attendance at the concurrent screenings in the east part of Berlin. Only 9,426 people attended the 70 screenings at the Kino International, which amounted to only 25% capacity. The Berlinale was still popular with the professionals however – 8,342 accreditations set a new record. How could these numbers be explained? The future of the Berlinale was a perplexing question.