1993

43rd Berlin International Film Festival

February 11 – 22, 1993

“You don’t necessarily need an evil will for a catastrophe to occur. It can suffice to be intellectually overtaxed.” – Jan Ross in the “Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung” on the main character in Nick Gomez’s Laws of Gravity, which ran in the Forum.

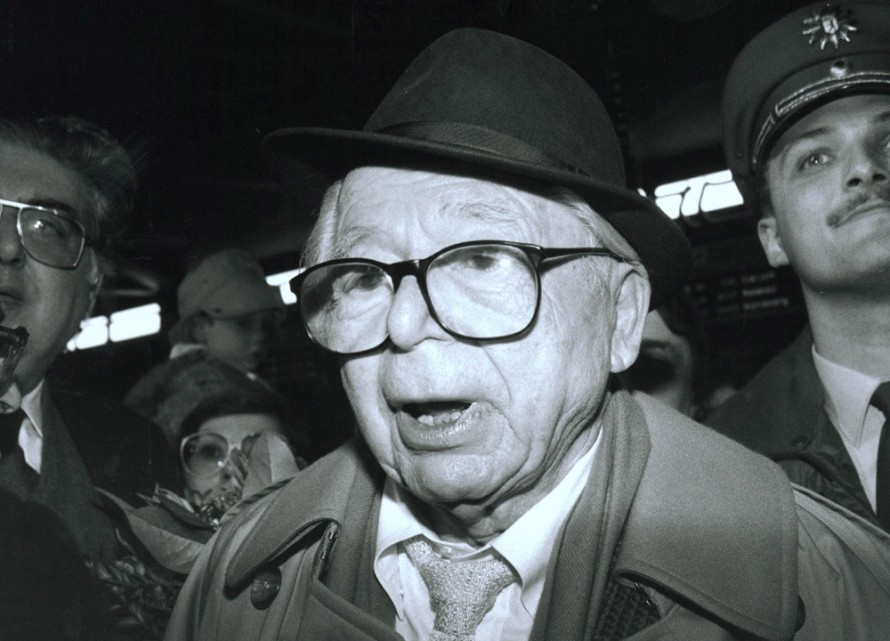

Received the Honorary Golden Bear in 1993: Billy Wilder

It could have got better, and it got

The 1992 Berlinale had been considered a disappointment for the most part. In 1993 the festival managed to regain a degree of sympathy and trust. An old accusation had reared its head again: that Hollywood films had too strong a presence at the Berlinale. This was countered this year with a very international and often absorbing programme.

In the Competition ran films which were convincing in their own way and were as varied as Ang Lee’s Hsi Yen | The Wedding Banquet, Emir Kusturica’s Arizona Dream, Jacques Doillon’s Le Jeune Werther | Young Werther, Constantin Costa-Gavras’ La petite Apocalypse | The Little Apocalypse, Detlev Buck’s Wir können auch anders | No More Mr Nice Guy or the two African contributions Samba Traoré by Idrissa Ouédraogos from Burkina Faso and Sankofa by Haile Gerima, a co-production with participation from Germany, USA, Ghana and Burkina Faso.

Changeover in the Panorama

Changeover in Panorama: Wieland Speck gets off to a good start

The stripped down Panorama was also received well. Filmmaker Wieland Speck had already assisted with the organization of the Panorama and now took over as director of the section from the gravely ill Manfred Salzgeber. He had already left his signature on the 1992 festival. Now under his management, the Panorama streamlined its profile and concentrated on its strengths: international art house productions, controversial themes and a strong presence of gay and lesbian filmmaking.

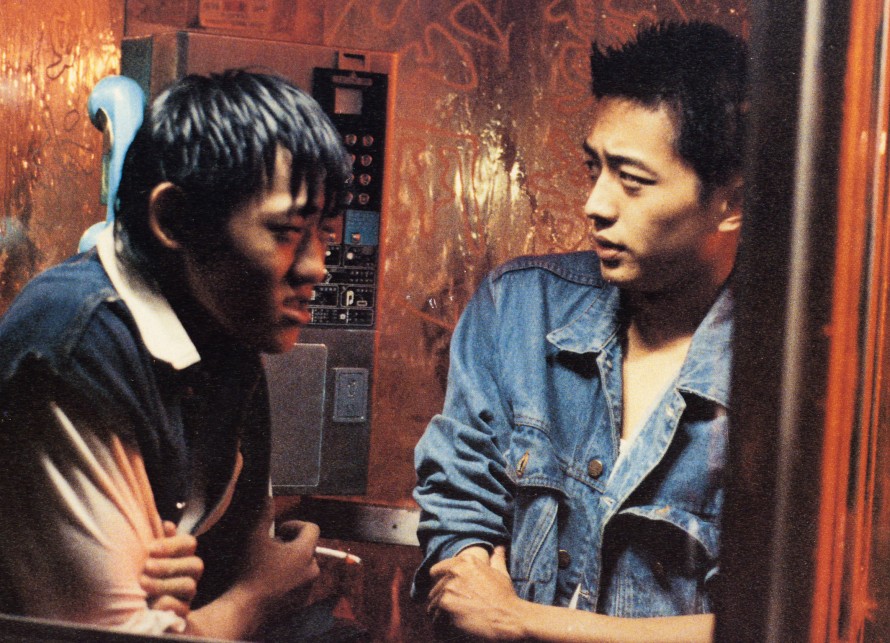

Stylistically speaking, the section sometimes seemed keen on building a consensus and was more closely oriented towards the Competition, while remaining provocative like the Forum, without ever stepping on its turf. Audience favourites like Woody Allen’s Husbands and Wives, Cameron Crowe’s Singles, Robert Rodriguez’ El Mariachi and young Tsai Ming Liang's second film Ching Shao Nien Na Cha | Rebels of the Neon God ran in the new programme series “Panorama Special”. John Sayle’s Passion Fish, Derek Jarman’s Wittgenstein, Katja von Garnier’s Abgeschminkt! | Making Up! or Vera Chytilová’s Dedictiví aneb Kurvahosigutntag | The Inheritance or Fuckoffguysgoodbye defined the territory addressed by the programme series “Art & Essai”.

New ways out of the dilemma "assimilation or resignation”

In its entirety, the festival programme proved that in filmmaking around the world it was possible to preserve original and also regional forms of storytelling despite increasing commercial pressure. The programme showed that between conformism and resignation there were still a dazzling number of alternative ways of dealing with economic hegemonies – as seen in the noticeable high number of multinational co-productions in the Berlinale programme this year. And especially the films themselves, their humour and their irony, made 1993 a hopeful year for the Berlinale.

Arizona Dreaming: Emir Kusturica, Johnny Depp, Vincent Gallo

The opening film, Emir Kusturica’s Arizona Dream, with its fantasy and humor, its at once exalted and melancholic tone, sent a challenging signal. The film playfully and ironically referenced the oft bemoaned Americanisation of images. Assi Dayan’s Ha Chayim Alpy Agfa | Life According to Agfa and Ang Lee’s Hsi Yen | The Wedding Banquet were similarly extroverted and daring in their storytelling. Both films didn’t shy away from giving equal treatment to both the comedy and tragedy in the lives of their characters and therefore stood for a contemporary narrative that could survive without a healthy dose of defiance.

Dancing on the ruins: The new Eastern European cinema

Exemplary for this tendency was also Dusan Makavejev’s Gorilla Bathes at Noon, in which the Yugoslavian director shows how a Russian soldier misses the withdrawal from Berlin and gets lost in the city carrying a Soviet flag – a placeless and timeless character who is desperately trying to cement the cracks in history and in his own life story. It was also a farce and an unintentional commentary on Berlin’s treatment of its recent history: a commission deals with the issue of what to do with the Soviet monuments in the city. The Lenin memorial upon which Makavejev’s anti-hero raises his flag was to disappear just a short time later.

Other Eastern European works were angrier, more uncompromising and pessimistic, such as the Rumanian Competition entry Patul Conjugal | The Conjugal Bed by Mircea Daneliuc, which provides an unsavoury and outspoken snapshot of an utterly corrupt country. It’s a film that “for a moment pushes aside the abundance of images at a festival, because it so desperately tells of the death of all feeling and the imperialism of hard currencies,” wrote Josef Schnelle in the “Frankfurter Rundschau”. Betrayed dreams, the wreckage of ideology and the feeling of being abandoned by history, were the dominant themes in several Rumanian films in the Panorama and Forum.

Jen Chang-pin and Chen Chao-jung in Ching shao nien na cha

Opportunity, liberation and collapse were accompanied by pain and the reappearance of unhealed wounds. The war in the Balkans had started to become a European reality. Under the title “Never again war”, a special screening of Un jour dans la Mort de Sarajevo | A Day in the Death of Sarajevo was held, a forthright commentary on the civil war in the former Yugoslavia, which fell flat with many commentators because of its partisanship and pathos. In another special screening, Requiem by Reni Merten and Walter Martis was shown, a “musical cinematic poem” in memory of the millions of people that died on the battlefields of Europe in the 20th century.

The Kinderfilmfest also strikes a serious tone

History was also present in the Kinderfilmfest. Renate Zylla showed courage in her decision to invite the Turkmen film Angelotchek, sdelai radost | Little Angel, Make A Joy by Usman Saparov. The movie is set during the Second World War and tells the story of the expulsion of ethnic German settlers from a Turkmen village. The programme of the Kinderfilmfest has long distinguished itself by showing films “that take children seriously, without overwhelming them.” All three juries, including the children’s jury, honour this commitment, in the fact that they consider Saparov’s sensitive yet difficult movie in their award decisions.