2016 | Forum

Global Movements

Flight and forced migration are among the central topics of the 2016 Forum. In this interview, section head Christoph Terhechte also discusses individual happiness-seekers, Chinese genre cinema, modern forms of slavery and the punk years of Japanese films.

Deadweight by Axel Koenzen

Looking at the programme, one gets the impression that the topic of refugees has arrived most powerfully in the Forum at the 66th Berlinale. Is that correct?

There are actually quite a few films on this topic. All works which have already been thought about for a long time, or even made, and which tackle the question of what kind of images can be found, which approaches to and perspectives on the subject exist. The films in this year’s Forum programme find very diverse answers to this.

A film which deals with the topic directly is Havarie. What distinguishes Philip Scheffner’s work?

Havarie renounces illustration. Philip Scheffner’s research revolved around a 3-minute found video clip which shows an inflatable dinghy disabled and adrift in the Mediterranean. The results of this meticulous research can be heard on the soundtrack – the occupiers of the boat, the crew of a cruise ship from which a tourist filmed the video, and so on. The film gives the viewer the opportunity to fill the statements with their own imaginings and does not force a predetermined image upon them – so we are given the chance to think for ourselves. Many documentary or hybrid works in the programme employ such a decoupling of image and sound. The text is not misused in order to explain the images and the images are not misused in order to illustrate the texts. Instead, both levels occupy their own independent territory.

Philip Scheffner has a second film in this year’s programme which also addresses the topic of refugees. And-Ek Ghes… builds upon Revision (Forum 2012): the Velcu Roma family has now arrived in Germany. Scheffner relinquishes a part of the filmmaker’s control – also a production strategy in many other films in the programme – and makes Colorado Velcu his co-director. Being part of the subject matter himself, Velcu films and produces what happens to his family in Germany. Which is very humorous and entertaining. This technique of relinquishing control in order to gain something is also used by Moritz Siebert and Estephan Wagner in Les Sauteurs (Those Who Jump). Their co-director Abou Bakar Sidibé is a refugee from Mali who is sitting tight before the gigantic border fortifications surrounding the Spanish enclave of Melilla in northern Morocco and who hopes to conquer the fences. He contributes images to this film which the European directors would never have been able to find.

Tales of Two Who Dreamt by Nicolás Pereda and Andrea Bussmann

The topic of refugees in the programme is spread across the globe. Tales of Two Who Dreamt by Nicolás Pereda and Andrea Bussmann and Manazil bela abwab (Houses without Doors) also depict people who must leave their homeland...

Tales of Two Who Dreamt is a Canadian-Mexican co-production filmed with Hungarian Roma in Toronto – it could scarcely be any more international. A married couple are in a tower-block preparing for a hearing about their family’s residence status. The building on the edge of the city appears to be abandoned and harbours many stories. Their rehearsals for the hearing are blended with these stories and a conglomerate of things heard, self-experienced and downright myths is created. Again, the characters contribute their own stories, producing and shaping the film not just as subjects but also as creators.

In the Syrian Manazil bela abwab, Avo Kaprealian documents the scenes unfolding in the streets at the beginning of the war by filming from his balcony. Over a long period of time you begin to sense how the war is intruding ever more powerfully into everyday life in the city of Aleppo, until finally the decision is made to flee. In the process, Manazil bela abwab is playing with the repetition of history because, generations ago, Avo Kaprealian’s family escaped the Turkish genocide of the Armenians. In Aleppo, an Armenian enclave in Syria emerged. Kaprealian incorporates the new flight – this time from Syria to Lebanon – and the parallels which exist by using film clips about the topic of the Armenian genocide. He combines associative observations with historical film footage.

Are there connections between the individual films engaging with the topic of flight?

There are many connections, though it’s up to the viewer to discover them. But generally, no duplications should occur. We’re trying to find works which are as diverse as possible, sometimes even contradictory in the way they approach a subject matter or the perspectives they offer. Only through that is a programme created.

Fei cui zhi cheng (City of Jade) by Midi Z

Searchers for Happiness and Slaves

Eldorado XXI and Fei cui zhi cheng (City of Jade) tell of working conditions in remote regions of the world. Are these two films comparable?

Eldorado XXI by Salomé Lamas depicts Peruvian gold-miners at 5,100 metres above sea-level. Certain similarities can be found with the Burmese jade mines portrayed by Midi Z in Fei cui zhi cheng. However, the films address entirely different points of departure. Midi Z tells the story of his brother who has been seeking his fortune in the mines for years. The prospecting work is arduous and dangerous and can only be achieved through massive drug consumption. Nevertheless, even after decades, his brother still has his hopes set on great riches. Fei cui zhi cheng shows an individual search for happiness in contrast to Eldorado XXI which is about organised exploitation.

As in Makhdoumin (Maid for Each)?

In this case it is about modern slavery. In Lebanon, practically every middle-class household has a South East Asian or African maid. They are exploited, the situation frequently ends in physical or sexual abuse. The young director Maher Abi Samra observes that this phenomenon has now also been transferred to his generation and shows the “work” of agencies who organise this abuse and place these modern slaves with their masters. This is a global problem. Conditions are supposed to be even worse in Saudi Arabia. In Hong Kong there are tens of thousands of Filipino housemaids who meet in Hong Kong Central every Sunday just to have something resembling a social life once a week.

Vlažnost (Humidity) by Nikola Ljuca and Inertia by Idan Haguel sound like two sides of the same coin...

Yes, there are some interesting parallels. The protagonist in the Serbian Vlažnost is a young man from the nouveau riche milieu who is leading an empty high society life. His wife suddenly disappears but he doesn’t address this disappearance at all and just continues with his superficial existence. Vlažnost depicts a society in which it is no longer about people but all about appearances, about functioning in an extreme capitalist society in which the rich just safeguard their material possessions.

The Israeli film Inertia, on the other hand, is a film about a woman who at some point wakes from a nightmare and realises that her husband has gone missing. At first she searches for him before it dawns on her that she can actually live just as well without him. Both films utilise the motif of a sudden disappearance as a metaphor for a society in which too many things have gone awry, a society which is no longer grounded.

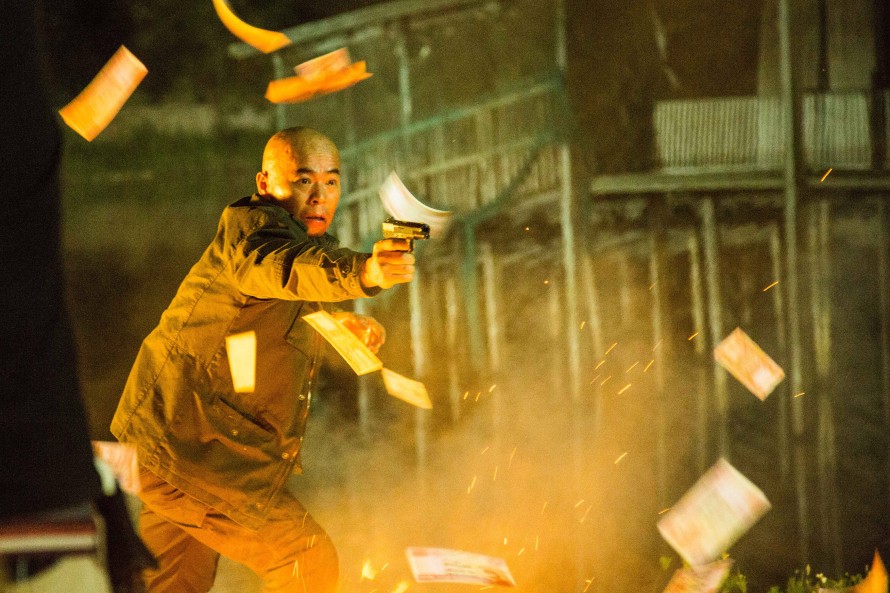

Trivisa by Vicky Wong, Jevons Au and Frank Hui

Genre Cinema in Hong Kong and China

Is Hong Kong genre cinema experiencing a revival with Trivisa?

Trivisa is genre cinema celebrating with relish its own history which has been relegated to the past. Hong Kong gangster films blossomed in the 1990s but then ground to a halt when the British colony reverted to China. Today, filmmakers in Hong Kong produce for the Chinese market and no longer cultivate this original, very distinctive cinema. There are, however, exceptions like Johnny To who produced Trivisa. The film directly addresses the handing over of power in 1997. He depicts the situation amongst organised crime, the Triads, which had to look for new business models after the change. Trivisa is made by three young directors, each of whom stage the story of one of the protagonists.

Has the genre film completely disappeared from China?

Not quite, but Chinese cinema doesn’t have a big genre tradition. Aside from ghost stories, which are not permitted because ghosts are incompatible with the materialistic theories of the communist authorities. A film like Zhi fan ye mao (Life after Life) by Zhang Hanyi has no chance of appearing in cinemas in China even though the ghost motif is actually used as a metaphor. The film tells the story of a woman who returns to the world in the body of her own son in order to make her husband replant a tree, meaning the film is referring to the changes and the environmental catastrophe in the country.

Japanese Punk Films: High-School-Terror by Macoto Tezka (1979), Tokyo Cabbageman K by Akira Ogata (1980) and The Adventure of Denchu-Kozo by Shinya Tsukamoto (1988)

Japanese Anarchism in 8mm

You are showing a series of Japanese works from 1977 to 1990 under the title “Hachimiri Madness - Japanese Indies from the Punk Years”. What is the background of these films?

Whilst the medium of video was being discovered in America and Europe in the late 1970s and early 1980s, Japanese filmmakers were having a fling with the 8mm format until the early 1990s. Most of the now famous directors, like Sion Sono and Masashi Yamamoto, made their first feature films on 8mm. The works from that time have almost completely disappeared because the material is difficult to copy and was never subtitled. Keiko Araki from PIA Film Festival in Tokyo, where the films were screened in the 1980s, Jacob Wong from Hong Kong Film Festival and I have burrowed through the archive, viewed many of these films and decided to digitise some of them in 2K and furnish them with English subtitles.

The title of the series, “Japanese Indies from the Punk Years”, refers less to the music than to the rebellious attitude of punk. In their anarchy and madness, the films constitute an interesting contrast to the works of young filmmakers today, to their cautiousness and introspection. Like Aru michi (A Road) by Daichi Sugimoto. At 22 years old, he is probably the youngest filmmaker to be debuting with a feature film at the Berlinale – and he is celebrating the nostalgia for childhood! For him in his early 20s, life is already over because now the seriousness of adult life begins and so he is recalling the beautiful moments of his childhood. Sugimoto is fully aware of the inherent contradiction and he demonstrates this schizophrenia with great sensitivity. But it’s a stark contrast to the mad acts from the 1980s.

Was there a reason for this anarchist outburst?

It was more than an outburst. The punk movement ruptured a lot worldwide. The utopian ideas of the 1968 movement quickly ended in disillusion both in the West and in Japan. Even though many things changed over the decades, the anticipated revolution never arrived. The punk movement said “Fuck it, we’ll do our own thing”. Anarchism and “no future” instead of proletarian revolution.

Le Fils de Joseph by Eugène Green

Does this anarchism still exist today? Le Fils de Joseph and Barakah yoqabil Barakah (Barakah Meets Barakah) by Mahmoud Sabbagh sound like they delight in destroying conventions...

Le Fils de Joseph is, in the very least, highly idiosyncratic. Director Eugène Green lets his actors declaim as in French baroque theatre. The artificiality of the acting style forms a sharp contrast to the depiction of everyday life in the film. It tells the story of a young man who wants to know who his father is. This is carried out with a lot of humour, although also grounded in myth: Abraham and Isaac are wildly combined with other elements.

Barakah yoqabil Barakah is a classic romantic comedy, boy meets girl. In Saudi Arabia two impossibilities stand in the way of this: one is that the country’s strict interpretation of Islam does not provide for any form of dating and flirting. The other is that the medium itself, film, doesn’t really exist. The country doesn’t have a film, entertainment or visual culture. And yet Mahmut Sabbah produces a classic romantic comedy which breaks both taboos. There are lots of women with long flowing hair not covered by a hijab and many more things which do not tally with our image of Saudi Arabia. A very quirky comedy.