2018 | Forum

Looking Back to the Future

A focus on the past is a central theme in 2018 for both the Forum and Forum Expanded. In this interview, Forum section head Christoph Terhechte expands on this focus and speaks about the rebellious spirit of Japanese cinema and forms of alternative historiography.

11 x 14 by James Benning

This year the Forum Expanded exhibition begins with Nesrine Kohdr’s Extended Sea. The work is composed of a single take lasting 705 minutes. Is it representative of the kind of experiment with form that make the Forum what it is?

The works in the Forum don’t necessarily have to be quite so extreme but we do insist on an awareness of form. The section is defined by the requirement that form must never lag behind content. Of course, it’s important to us how the films locate themselves in society and their connection to reality. But a decisive factor is that they find an adequate form for their stories. Form and content must be given an equal footing. That is, for me, the essence of our work in the Forum.

In this context, for me 11 x 14 by James Benning also particularly stands out...

James Benning has been with us in the Forum since the 1970s. 11 x 14 is his first feature-length film and narrative theory brought to life. He has succeeded in using staged images – as opposed to dialogue, which is normally the case in narrative cinema – to create a narrative structure. In the 1970s, directors like James Benning created the foundations for an understanding of images which today’s art-house cinema draws on as a matter of course. In the very least, this happens in a cinema that has uncoupled itself from theatre and literature and understands film as an independent form of art and narrative.

Teatro de guerra (Theatre of War) by Lola Arias

Lest We Forget

Contemplating the future by looking back into the past appears to be a motif of this year’s programme...

This looking back to the future can indeed be found in an unusually large number of films. Ruth Beckermann, for example, has edited Waldheims Walzer (The Waldheim Waltz) from footage she shot in the 1980s. This has resulted in a film about the election campaign of Kurt Waldheim who, when standing for President of Austria in 1986, wanted to have his Nazi past forgotten. It fits in very well with the current state of affairs in Austria.

Christina Konrad unfolds her theme in Unas preguntas (One or Two Questions) in a similar way to Beckermann. Konrad is also working with footage she shot in the 1980s and hasn’t used up to this point. Now an almost four-hour-long documentary has arisen which questions the meaning and purpose of remembering. Her subject matter is the opposition to an amnesty granted by the Uruguayan government in 1986 to the perpetrators of the military dictatorship. The film reflects on the connection between amnesty and amnesia and we read it as a plea that, instead of history being placed in the past, memories should be reappraised and accountability exercised. By using this material today, Konrad creates a doubling effect: on the one hand, the film is about dealing with the past; on the other, it is about dealing with the material that was created in the past. Unas preguntas advocates looking back to be able to see the future.

This idea permeates the entire programme this year. Teatro de guerra (Theatre of War) by Lola Arias proceeds in a similar way. Also in connection with a military dictatorship – this one in Argentina which has never permitted its perpetrators to be challenged. The work is a staged documentary in which Argentine and British veterans of the Falklands / Malvinas conflict encounter each other.

La casa lobo (The Wolf House) by Cristóbal León and Joaquín Cociña

La casa lobo (The Wolf House) by Cristóbal León and Joaquín Cociña, contains another, very different form of looking back. The film uses stop motion animation. The background is, once again, a military dictatorship in Latin America, this time in Chile. A girl flees from the German Colonia Dignidad and, in a dark forest, finds a house in which everything is in a constant state of metamorphosis - including herself. The film uses elements from German fairy tales and, once again, is about reappraisal and remembering.

Is this topic also present in the fiction films?

Yes. The range is very wide. Our Madness by João Viana tells of a psychiatric clinic in Maputo and the ghosts of a colonial past which haunt people’s minds to this day. Wieża. Jasny dzień. (Tower. A Bright Day.) by Jagoda Szelc reveals from the outset that it is based on events in the near future. It shows a family whose unspoken and repressed secrets from the past make it impossible to master this near future.

Isabel Abreu and Eduardo Aguilar in Mariphasa by Sandro Aguilar

Quo vadis?

Does this concentration on a single topic say something about the current state of the world?

Absolutely. Our work as curators means recognising a common theme in the creations of the filmmakers and to make this clear in the compilation of the programme. And a focus on the past is something that is intensively preoccupying filmmakers at the moment, precisely because the view of the future is very much blocked across the world. We can’t really imagine what our civilisation will look like in 20 or 50 years time. To find answers to this question, we must fully engage with the past because it contains the root causes of what is happening today. This is the prerequisite for future utopian visions.

With regards to the topic of the future, it is interesting that in a total of three films – Last Child, Mariphasa and Syn (The Son) – children die...

All three films are about dealing with a death in the family. Death is a violent caesura and always prompts questions about the meaning of life. And the meaning of life is, in turn, connected to further questions: how should we live? How can we shape the future? How can we return to having a positive, optimistic and utopian vision of it?

In the programme the past is a motif, but obviously the entire programme is not composed of this single topic. Rather than putting on a theme night, we are seeking to compile a programme in which highly contrasting colours create a tapestry through which a motif may be threaded.

L'empire de la perfection (In the Realm of Perfection) by Julien Faraut

In view of the films we have already discussed, this year’s programme sounds a little bleak...

Quite the reverse. The programme contains many very humorous films: offbeat documentaries like L’empire de la perfection (In the Realm of Perfection) by Julien Faraut, which dissects the character of John McEnroe and his tennis playing. Fotbal infinit (Infinite Football) by Corneliu Porumboiu is incredibly funny because it portrays a totally bizarre personality. Motivated by his personal story – as a young man he suffered a grave football-related injury – he now is setting out to do everything he can to redefine the rules of the game. The Green Fog by Guy Maddin, Evan Johnson and Galen Johnson is an extremely entertaining but also odd film which uses set pieces from the history of film and television and creates a new story from found footage shot in the San Francisco Bay area. Even if none of the films can be defined as comedies per se, they contain many comedic - grotesque, humorous and visually striking – elements. The programme thrives on being a mixture. To screen only bleak films wouldn’t work.

Aira Sunohara and Maiko Mineo in Amiko by Yoko Yamanaka

The Spirit of Anarchy

Nevertheless, a character like Amiko and her wildness and anarchy feel like rather an exception...

Yes, that’s true. It’s something that has also struck me. Amiko is a debut film, a first stab at cinema. At 20 years old, Yoko Yamanaka is the youngest director in the entire festival. I really hope that she makes more films because she clearly has a huge imagination and possesses a type of cheekiness and nonconformity that has become very rare. It was present, though, in the Japanese films of the 1980s which screened two years ago in the “Hachimiri Madness – Japanese Indies from the Punk Years” programme: 8 mm films that documented this rebellious spirit. It doesn’t exist anymore today. When a 20 year old like Yoko Yamanaka shines with this spirit, it is already a revelation. Amiko is a film which, at first glance, you might not expect to see in the Forum if you are looking for the grand designs of experimental film art here. But I find that films like Amiko belong to us: I gladly place this rebelliousness, untamed strength and imperfection alongside old masters like James Benning.

Can this anarchy and dynamism be found in the Japanese “pinku eiga” films you are screening this year?

The “pinku eiga” were originally a purely commercial undertaking: low-budget films with erotic content. But, very quickly, young directors realised that in this genre, provided they followed the rules - by presenting enough sex scenes – they could do whatever they wanted. This resulted in films that called for the government to be overthrown, avant-garde and genre cinema that had nothing to do with the purely commercial imperative that “sex sells” any more. With Inflatable Sex Doll of the Wastelands, Atsushi Yamatoya even managed to make a film in this genre entirely without the traditional sex scenes and instead made voyeurism the subject matter. And it somehow got through. It’s similar to the ways in which directors of the European New Wave made genre films – going totally against the grain. Beyond the required scenes, the “pinku eiga” directors experimented and created a radical cinema. And it worked so well that, up to the late 1980s, entire generations of filmmakers grew up in this genre. However, the “pinku eiga” films have a very different status as the Hachimiri films which openly protested against society and conventions. In “pinku eiga” the system was being utilised in order to be able to make films at all.

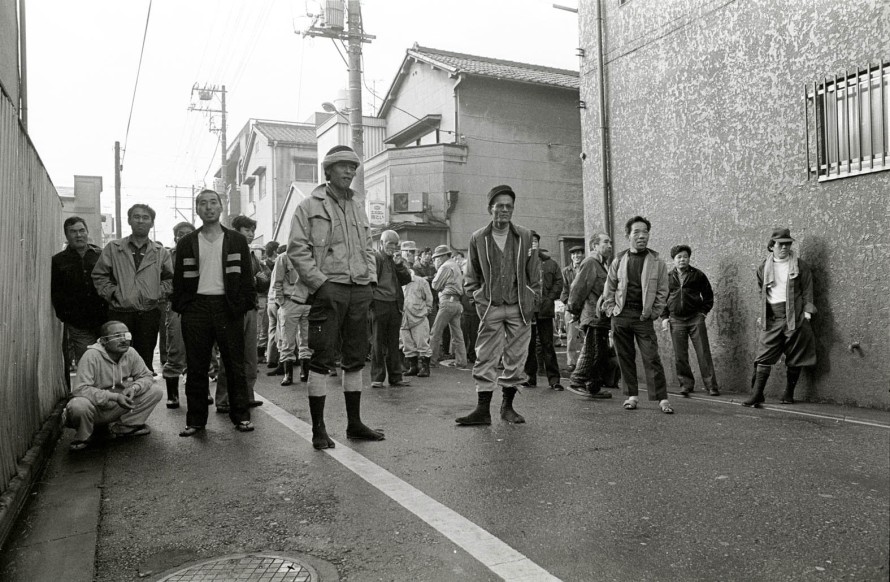

Yama – Attack to Attack by Mitsuo Sato and Kyoichi Yamaoka

Alternative (Film) Historiography

Are these Special Screenings also a part of the archive work which is central to the Forum?

Yes. And they are closely connected to the theme of remembering in this year’s programme and to the work of the Kino Arsenal and its history. Ever since its inception, the Forum has taken on the distribution of the films it has screened. This has resulted in a huge archive which is often the only place in the world where a copy of a certain film exists. And we now restore films that are often defined as “marginal” which is proof that there is a big interest in engaging with the so-called “margins” of filmmaking. We are fighting against the dominant idea of film historiography which is defined by a very narrow canon and which dates from a time when people believed that all films of any significance were produced in the West. Everything outside of this perspective was marginalised. And this in spite of the fact that works from the “margins” often allow you to perceive a lot more than those from a narrow canon. For this reason, we are showing in the Specials essential films which have never been properly appreciated and have almost been forgotten already. And also works like, for example, the Geschichten vom Kübelkind (Stories of the Dumpster Kid) by Edgar Reitz and Ula Stöckl, which never wished to be integrated in the usual film distribution channels in the first place and instead invented alternatives – in this case, the pub cinema – which this year we are recreating in the silent green Kulturquartier and which was the precursor of the many micro-cinemas popping up today.

Does this alternative historiography only apply to film history?

Every film is also an alternative look at social realities. A good example is Yama – Attack to Attack by Mitsuo Sato and Kyoichi Yamaoka. The directors were both murdered because they documented the fate of day labourers in 1980s Tokyo. This interfered with the interests of the Yakuza who were responsible for this form of exploitation. Yama – Attack to Attack is not only an alternative form of film historiography because it is a milestone of Japanese political documentary which is scarcely known here. It is simultaneously a work of alternative historiography in general because it provides a totally unfamiliar image of Japan and Tokyo.