2018 | Retrospective

“We Do Want to Expand Perceptions of the Era’s Cinema”

Section head Rainer Rother talks about the film selection process, the relevance of the subject matter, and the outlook on the future reflected in the Retrospective “Weimar Cinema Revisited”.

Lillebil Christensen and Leopold von Ledebur in Christian Wahnschaffe, Teil 1: Weltbrand (Christian Wahnschaffe, Part 1: World Afire) by Urban Gad

You are showing almost 30 films in the Retrospective. However, very few of them are mentioned in classic accounts of Weimar-era cinema. In his book “From Caligari to Hitler”, Siegfried Kracauer deals with just ten of the films being shown in the Retrospective, while in “The Haunted Screen”, Lotte Eisner only mentions six or seven. Are you trying to deconstruct the canon?

In fact, we do want to expand perceptions of the era’s cinema. We had a few important criteria when we approached the subject – where we could find interesting discoveries outside of the canon, and which films still hold up so well today that we want Berlinale audiences to see them. With that in mind, we looked at archival copies of rarely-shown films, as well as works so recently restored that it is only now possible to even screen those films in their entirety again. As one example of the latter, we selected a two-part film directed by Urban Gad that had been largely forgotten and has now been reconstructed, “Christian Wahnschaffe”, based on Jakob Wasserman’s two-volume 1919 novel.: Christian Wahnschaffe, Teil 1: Weltbrand (Christian Wahnschaffe, Part 1: World Afire, 1920) and Christian Wahnschaffe, Teil 2: Die Flucht aus dem goldenen Kerker (Christian Wahnschaffe, Part 2: The Escape from the Golden Prison, 1921).

But the title of the Retrospective, “Weimar Cinema Revisited” has yet another meaning for us. For a long time, even many of the core works of the period were only available as badly deteriorated prints. The increasing number of high-quality digital restorations has now made it possible to re-visit films we thought were familiar. It’s incredibly exciting to suddenly see a film you thought you knew in a version that is possibly quite close in quality to the original release print.

When you are preparing a Retrospective, you’re in contact with numerous institutions. To what extent do you benefit from previous initiatives that have re-evaluated the history of film in Germany?

The foundation of this Retrospective is the work done by film archives. They do not limit themselves to preserving only masterpieces; their goal is to make the entire spectrum of Weimar-era cinema available. During our pre-selection process, we were inspired by, among others, the series of 15 silent films curated by Hamburg’s CineGraph, “The Other Weimar”, at the 2007 Pordenone Silent Film Festival, as well as the 2010/2011 retrospective “Weimar Cinema, 1919–1933: Daydreams and Nightmares” at New York’s Museum of Modern Art, with which the Deutsche Kinemathek was also involved. The series “Wiederentdeckt” (“Rediscovered”) was also helpful – CineGraph Babelsberg has been showing lesser-known films from the Weimar period under that banner in Berlin’s Zeughaus cinema for 25 years.

Jack Trevor, Brigitte Helm and Anita Haldern in G. W. Pabst's Abwege (The Devious Path)

Between the two world wars, the German film industry was the most productive in Europe. So the pool of films available to you must have been correspondingly large. What thematic aspects did you take into account during the selection process?

Germany in the 1920s had the greatest number of cinemas in Europe, and produced films for mass audiences of as many as two million moviegoers per day, most of whom went to see light entertainment. We were particularly interested in themes that run through the differing genres and production styles of that flourishing film industry. We had more than 200 films on the initial long list. From the beginning, we excluded the 50 best-known Weimar films – unless they had been recently restored, as was the case with G. W. Pabst’s Abwege (The Devious Path, 1928), as well as with Kameradschaft (Comradeship, 1931). In the end, we picked three thematic focal points and concentrated on them – “Quotidian”, “History”, and “Exotic”. We also paid special attention to experimental approaches to the actual design and creation of a film, for instance, in the use of sound, which was just being introduced at that time.

Brüder (Brothers) by Werner Hochbaum

In what form is the quotidian expressed in the selected films? The majority of films you are screening are narratives, not documentary. Or are there also hybrids?

Under the influence of the New Objectivity, many narrative films during that period integrated reality into their scenarios. That is true, for instance, of Werner Hochbaum’s Brüder (Brothers, 1929), with a cast completely made up of non-professional actors. It was set during the 1896/1897 Hamburg dockworkers’ strike and portrayed everyday events at the harbour, which lent it a strong documentary style and substance. Many of the films aimed at addressing social issues. For instance, in his childhood tragedy set in Berlin, Die Unehelichen (Children of no Importance, 1925), director Gerhard Lamprecht wanted to realistically depict the life of different classes of society – labourers and the bourgeoisie. Alexis Granowsky’s Das Lied vom Leben (The Song of Life, 1931), which has strong experimental tendencies, triggered a scandal with the censors mainly because it had documentary footage of a delivery room birth. Then there is Sprengbagger 1010 (Blast Excavator 1010, Karl-Ludwig Acház-Duisberg, 1929). With its “machine music” by Schönberg student Walter Gronostay, it was also a film experiment. Its depiction of the technical process of strip mining is extraordinarily close to the everyday reality, although the film otherwise lays no claim to realism. And then there are many films in which a melodramatic or a humorous story is interwoven with the quotidian. But the everyday is most directly reflected in one of the short film programmes. You see more or less unfiltered images of Berlin in ca. 1930; what you might have seen if you had roamed the city’s streets for a day. The tour goes to Wittenbergplatz in Markt in Berlin (Open-air Market in Berlin, Wilfried Basse, 1929) and to Alexanderplatz in Alexanderplatz Überrumpelt (Alexanderplatz Unawares, Peter Pewas, 1932–34), but also to more disreputable parts of the city in Polizeibericht Überfall (Police Report of Mugging, Ernö Metzner, 1928).

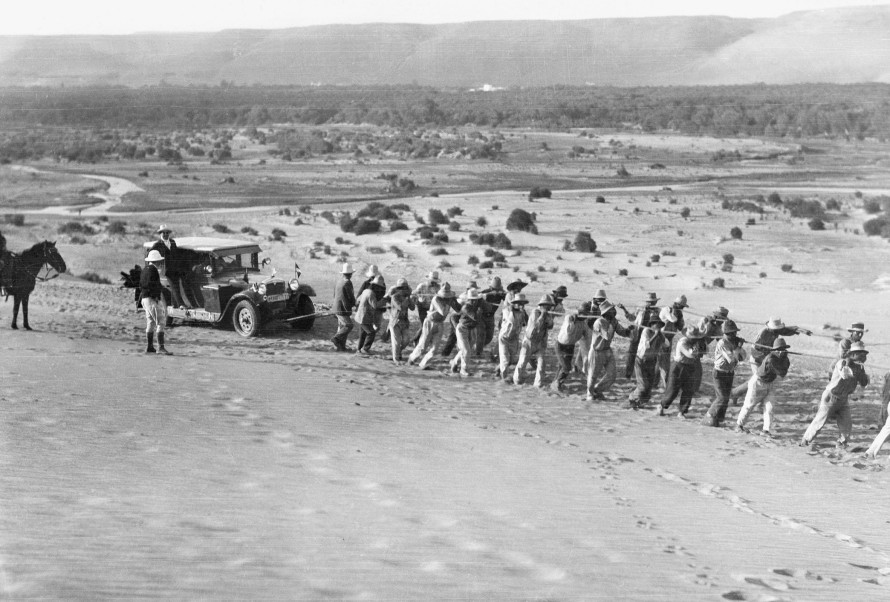

Im Auto durch zwei Welten (Across Two Worlds by Car) by Clärenore Stinnes and Carl-Axel Söderström

Which parts of the world do the exotic films take us to?

To almost all of them. Actually, in a single documentary alone, namely in Im Auto durch zwei Welten (Across Two Worlds by Car, Clärenore Stinnes, Carl-Axel Söderström, 1927 – 1931), about a round-the-world trip that Clärenore Stinnes actually took. It is a documentation of the exotic that, seen from our modern-day perspective, is as challenging as it is sometimes dubious. That is also true of Menschen im Busch (People in the Bush, Friedrich Dalsheim, Gulla Pfeffer, 1930), an ethnological study made in Togo. In a long opening sequence, we see the last governor of the former German colony speaking, and his racist and colonial view of the world is shocking to modern audiences. The ethnographer Gulla Pfeffer and expedition leader Friedrich Dalsheim then tread new ground, allowing the Togolese family at the centre of the film to speak, instead of providing off-camera narration. That ambiguity, that ambivalence – especially in documentary material about exotic themes – becomes very clear in the films. We tried to represent the diversity of genres, and to show the various cinematic tools used to get closer to those faraway realities. It ranges from the ethnographic approach of Menschen im Busch to the exotic-looking narrative film Opium (Robert Reinert, 1919), which was made almost entirely on a sound stage, with the Chinese characters portrayed by German actors. That film contains a mass of clichés – an image of Asia that owes more to the imagination and yearnings of the time than to reality.

Leni Riefenstahl in her film Das blaue Licht (The Blue Light)

But surprisingly, you count the Alps among the exotic locations.

The mountain film is also a form of exoticism, especially in the 1920s and early 1930s. Critic Béla Balázs was a great fan of the mountain epics directed by, say, Arnold Fanck, because to him they represented a genre that went well beyond the usual conventions of narrative film. For him, the plot was significantly less important than the depiction of a reality that was inaccessible to city-dwellers. He even co-wrote the script for Leni Riefenstahl’s fantastic mountain film Das blaue Licht (The Blue Light, 1932). The mountain drama Der Kampf ums Matterhorn (Fight for the Matterhorn, Mario Bonnard, Nunzio Malasomma, 1928), restored in 2016, is based on the true story of the first ascent. And it too, in the final analysis, depicts a world that at the time was extremely exotic for most people. Almost precisely as exotic, in fact, as the India we see in the narrative film Die Leuchte Asiens (The Light of Asia, Franz Osten, 1925), which relates episodes from the early life of Buddha, while also casting a tourist’s eye around the country.

The 1920s and early 1930s were a politically tumultuous and strife-filled period. Is that also reflected in the films?

Definitely. Das Lied vom Leben and Brothers make direct reference to the political situation at the time. When Hochbaum reconstructed a dockworkers’ strike that took place about 1900, he was simultaneously commenting on the political reality that the filmmaker himself was dealing with. I think even a charming sound film operetta such as Ihre Majestät die Liebe (Her Majesty, Love, Joe May, 1931) was addressing current events in its own way. It’s one of many film operettas that looked at a very difficult situation in society, and also reflected class relations. And a film like Die Unehelichen can most certainly be described as critical of society.

Der Katzensteg (Regina, or the Sins of the Father) by Gerhard Lamprecht

At that time, looking back at history was also often influenced by politics. What is the perspective of the Retrospective films on the historical past?

What the period films we selected have in common, as a rule, is that the main characters are anti-heroes, broken figures. We see that, for instance, in Heimkehr (Homecoming, Joe May, 1928), which is about men returning from World War I and what that homecoming meant for a woman who had waited years for her husband’s return. In Die andere Seite (The Other Side, Heinz Paul, 1931), Conrad Veidt plays a British officer who is badly traumatised by war and has turned to alcohol for solace. Without exception, these are characters who think about things, and who show their human, their tragic side. That’s what makes these films so powerful and still so interesting today. In that respect, Ludwig der Zweite, König von Bayern (Ludwig II of Bavaria, Wilhelm Dieterle, 1930) is one of the most moving of the films; it portrays the “fairy tale king” as a broken man, always on the verge of madness. Also most definitely worth seeing is Der Katzensteg (Regina, or the Sins of the Father, 1927) by Gerhard Lamprecht. We assume that Prussian films will follow an uninterrupted tradition of glorifying Prussian virtues. But that film is totally different – it has no sympathy for Prussian virtues; rather, it looks behind the facade and relates in bitter tones a story from the anti-Napoleonic wars. It is a renunciation of all glorification. We can even look at the period film Der Favorit der Königin (The Queen’s Favourite, Franz Seitz Sr, 1922), made by Munich’s Bavaria studios, which can be seen as a kind of answer to the large-scale productions coming out of Babelsberg. It’s set in 16th century England and in 1922, it was a rebuke to a present that was in tumult, and that demanded stories that exhibited ambivalence. That is why that epoch continues to be so fascinating, even now, and reminiscent of the present day. Those depictions of a polarised society are extremely topical.

Alle Kreise erfasst Tolirag (Tolirag Circles) by Oskar Fischinger (1933/34) is part of the short film programme “Experiments in Sound and Colour”

The years from 1918 to 1933 were also a time of dramatic technological developments in filmmaking. Is the Retrospective also screening films that showcase those technical innovations?

They are most charmingly evident in the short film programme “Experiments in Sound and Colour”. That selection includes, among others, work by avant-garde artists such as Hans Richter and Oskar Fischinger. The series begins with films from 1922 that used the methods available at the time to produce colour films – meaning tinting and hand colouring. Then come films that introduce new colour techniques that were developed in Germany at the end of the 1920s – among them, Sirius-Kleuren’s rare two-colour process. It’s like a continuation of our Technicolor Retrospective – the two-colour Technicolor process was developed back then in Hollywood; Ufacolor and Gasparcolor, which we are presenting here, were competing techniques. And Munich animator and sound filmmaker Rudolf Pfenninger was well ahead of his time, drawing sound waves on the film soundtrack by hand – “graphical sound” – to which later avant-gardists such as Malcolm McLaren would explicitly refer.

Erich Haußmann in Morgen beginnt das Leben (Life Begins Tomorrow) by Werner Hochbaum

The urban drama Morgen beginnt das Leben (Life Begins Tomorrow) is recognisably the latest film in the Retrospective. It is set on April 21, 1933 and was actually shot after January 30, meaning after Adolf Hitler became Chancellor. Why is it being shown in a Retrospective alongside films made during the Weimar Republic?

Morgen beginnt das Leben (Werner Hochbaum, 1933) is a film that took up the mantle of Weimar-era cinema in its visuals and its joy in experimentation. At the same time, it points up what was still possible to do on film, if only just, at the start of the Nazi dictatorship – a diversity that would be expunged not long thereafter. It makes us aware of what might have been seen in cinemas if that development had not been interrupted by the Nazis. It’s a kind of wrap-up for us.

Morgen beginnt das Leben is a good note upon which to take a look at the near future. What will be the consequences of the Retrospective for new discoveries in and of films?

We have reason to hope that our selection will inspire other festivals and repertory cinemas to show films from the programme. That includes numerous films that have never been shown outside of Germany, and which are now accessible to an international audience, thanks to the English subtitles done for the Berlinale. We’ve also kicked off another project with our selection. At this year´s Berlinale, we’re showing a 16 mm print of Der Katzensteg, but the film will soon be restored, based on surviving 35 mm material. That, of course, is one of the nicest things for a retrospective, when it can help give a new lease on life to an old film.