2020 | Artistic Director's Blog

Rebecca. Shadows from the Past.

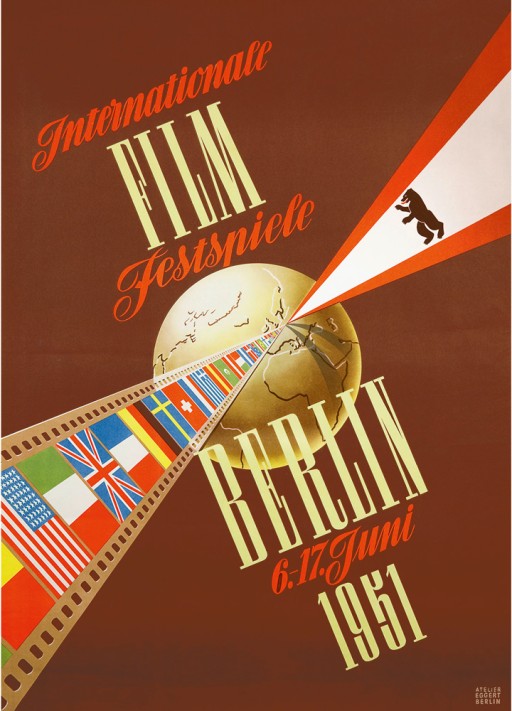

Hitchcock's Rebecca opened the first Berlin International Film Festival in 1951

Carlo Chatrian was Artistic Director of the Berlinale from June 2019 to March 2024. In his texts, he takes a personal approach to the festival, to outstanding filmmakers and the programme.

Rebecca arrived at the Berlinale ten years after its initial theatrical run. A lot had happened during those ten years, and while cinema – especially in post-war Berlin – has always been an entertaining means to escape from the present, it’s impossible not to imagine how that film, a mystery that opens on a once glorious villa now in ruins, affected the minds of viewers at the first Berlin Film Festival. Perhaps the organisers thought it a good idea to open the festival, which was born out of an Allied impulse, with a successful American film, the first American production of a certified master, which won an Oscar and showcased the talents of its leading lady, who attended the Berlinale screening. Or perhaps the idea of showing a film released in 1940 came with the innocent intention of turning back the clock, as if to heal the wounds of the past, albeit via an intermediary.

At its core, Rebecca is a story of reparation, dramatic though it may be. In spite of appearances, the humble maiden played to perfection by Joan Fontaine is an antidote, inserted into the beautiful yet chilly De Winter household to relieve the pain that pulsates beneath the golden sheen of luxury and the casual demeanour of the head of the family. As is often the case in Hitchcock’s films, the male character is weak and infirm. In Rebecca, Laurence Olivier’s charm conceals the situation, making the plot development less predictable. And yet all has already been said in the beautiful, completely unreal sequence where the two protagonists meet, and indiscreet female eyes penetrate the intimate and shameless sight of a man facing his secret. The scene opens with a shot of the sea, from above, with waves hitting the rocks. Through one of his famed camera movements, Hitch links the foam of the waves to the silhouette of a man on the edge of a precipice. This confirms that we are not inside a Caspar David Friedrich painting and man does not dominate the scene. On the contrary, he is subjugated, via a close-up of a foot on the edge and a musical crescendo.

Shortly before that moment, a voice had brought us beyond the mist, to Manderley, the home of the De Winters. Ravaged by time but still fully capable of seduction, it is the extension of its mistress, the invisible and omnipresent woman who gives the film its title. As hinted at by that extraordinary, twofold opening sequence, Rebecca is a film made up of fatuous fires and distant glows that light up and then fade away. Hitchock adopts a typically English sense of the Gothic to construct a film of shadows around that idea. Shadows, not ghosts – that would have been too obvious. No one feels or sees the traces of the past. No one wants to live in the past and yet everyone, be it master or servant, looks like a timeworn image. Even the story of the two newlyweds has been captured in a home movie, which gets jammed. Pleasure is not only apparently fleeting but a properly distant memory, while angry or frightened faces inhabit the present.

In terms of style, Rebecca deals strongly in chiaroscuro, to the extent of getting compared to German Expressionism. And while some shots may recall the famed lighting techniques from the 1920s, the underlying sense appears to be the polar opposite. Rebecca is bathed in an icy light, and the true dark side of reality never surfaces, much like Rebecca’s body or the feelings on Mrs. Danvers’ emotionless face. The simple and brilliant idea of building suspense based on an absence comes to a head in the film’s core scene, where the protagonist breaks into Rebecca’s room. Like a little girl in a Grimm fairy tale, Joan Fontaine opens the big white door, with a mixture of fear and desire, and finds herself inside a motionless space. The placement of the furniture is reminiscent of a sanctuary, a large veil protecting the sacred space. The room is in the shadows, shielded by thick curtains that wait to be lifted. Once they’ve been opened, we’re immersed in light filtered through other, thinner curtains. Like veils, they function as yet another screen, capturing and reframing a diffused light. The great empty space unveils, in lieu of an altar, a small table with a picture of Mr. De Winter (is he the deceased?) and a mirror where no images are reflected. The fluidity of the camera movements dictates the mise-en-scène, which deals in contrasts to reveal the lead character by default. In a room far too large, standing opposite a woman in black (the rigid Mrs. Danvers) who flaunts the opulence of Rebecca’s clothes, is the new Mrs. De Winter, who doesn’t even receive a first name. Wearing shabby and beige clothes, almost wordless, her gestures revealing a tactile discomfort, the second wife is crushed under the weight of the past, which is the weight of an absence. The scene ends with the two women, closer than ever, by the great white door. While the priestess resumes her being a shadow projected onto the curtains, the intruder leaves – returning to life. Outside, the sea bellows.

Carlo Chatrian