2016 | Panorama

Role Models

This year the Teddy Award – the only official queer film award at an A-festival – is celebrating its 30th birthday. Reason enough to ask Panorama curator Wieland Speck about the past and future of queer cinema. In this interview he also speaks about the persistent nature of the nuclear family, difficult births and a film-obsessed dictator.

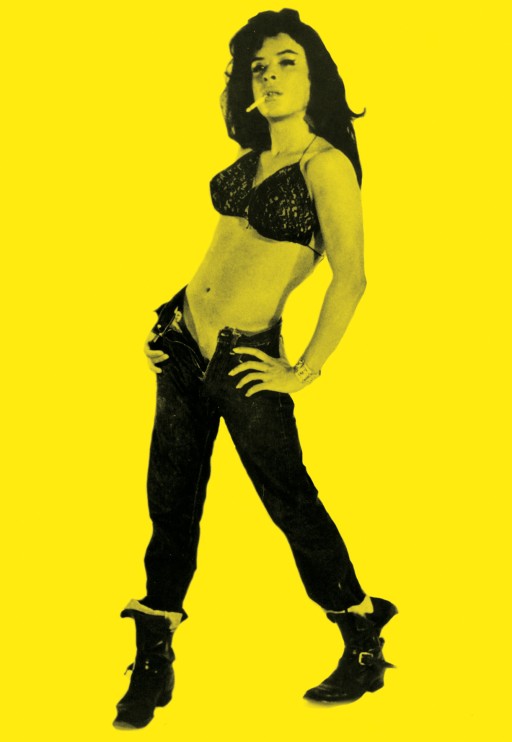

Je, tu, il, elle (I, You, He, She) by Chantal Akerman

In 2016 the Teddy queer film award is celebrating its 30th birthday. Is it possible, with regard to queerness, to speak of integration or even of a successfully completed integration?

I don’t believe integration is possible if it means the absorption of one into the other. In sexuality a fundamental human drive, an instinct, is at play which we can’t keep under control intellectually. You can’t just put up a few road signs in order to create peace on earth. Integration can only mean that the majority understands that the minority must be protected. To put it briefly: everybody may live and nobody is more right than anyone else. The political equality of rights must be established and their protection guaranteed – this is also with regards to sexual assaults on women, a current topic in the press.

But looking back over the last 30 years, much has been achieved, hasn’t it?

Yes. Humankind has figured out that they are humankind. This has developed further in some parts of the world than others, but there is still almost no place where equal rights have been achieved. Two gay men still can’t walk down the street like two heteros would. Nevertheless, it’s true that we have come a long way politically. And our task is to show this is. The Teddy, as an international beast which rises above the sexes and is really a big friendly monster, serves this aim.

Nunca vas a estar solo (You'll Never Be Alone) by Alex Anwandter

How important were the 17 films you’re screening in the "Teddy30” programme for the queer movement?

Making non-heterosexuality visible was and still is a giant step and one that has always been full of risk for those who dare to take it. One of the reasons we love film is because it can engender a political strength. The fighting power inherent in films is an impetus of the entire Panorama programme, independent of subject matter. And an inexhaustible impetus in the Panorama, is of course, the queer world.

In 2016 we have a film like Nunca vas a estar solo (You’ll Never Be Alone) by Alex Anwandter in the programme. It tells the story of a father, a single parent living with his 17-year-old son who is almost beaten to death – by boys from the neighbourhood who have known him since he was a child. A truly horrendous crime which only happens because the son is gay. The father must find a way to cope with living within this society and learn that he has absolutely no support.

Has queer cinema developed its own aesthetics?

Yes and no. When dealing with minority issues – whether they be sexual orientation or something else – there are always two sides i.e. the films always turn to both the inner and the outer. One objective is to develop the identity of a subculture, to strengthen and further it. Another is the aim to convey to the world that you are a part of it. Both these drives can be found in the programme for the Teddy anniversary. Also because we are going back to the time before the Teddy. Some really fantastic discoveries are being screened, films from the early 1970s by Chantal Akerman. One of the tasks of the Teddy is to connect tomorrow with yesterday in order to be able to grasp today and make something of it.

Já, Olga Hepnarová (I, Olga Hepnarova) by Tomas Weinreb and Petr Kazda

Of Families with or without Children

Regarding the 2016 programme: the, at least political, equality of the queer community seems to coincide with the demise of the classic nuclear family. Or is this a false impression?

I think we have so many “attempts at a family” in the programme because, in reality, the family is very stable and still dominates our thinking. The family ideal fights change with everything it has. So it is a very conservative matter. Many people founder on the family, but they can imagine a different way of life and realise that they don’t have to conform to the old model. However, to break free often means an uncertain future. Sometimes it is just about pure escape, which can have fatal consequences. Já, Olga Hepnarová (I, Olga Hepnarová) by Tomas Weinreb, which ends in the execution of its protagonist, is an example of this. The film also reveals the basics of radicalisation which, of course, doesn’t just occur in a vacuum: there is always something that enables it, enforces it. Já, Olga Hepnarová places this truly fatal situation under the microscope and, by using one biography, plays it out as an exemplary story. The eponymous main character lives in a functioning family but she cannot bear the way it functions.

Shelley by Ali Abbasi

The nuclear family as the “nucleus” of society also plays a role in the programme with regards to the crisis in its ability to reproduce. Shelley by Ali Abbasi seems to enact the horror of the nuclear family as a genre piece and brings to mind the devil children of the late 1970s...

Rosemary's Baby and so on... Yes, but this is a very modern couple, intellectual middle-class, nice people, everything organic. Though it is indeed a horror film, it expresses many truths about Europe. The couple has retreated from the active urban world, the woman has had to have a hysterectomy, they have to come to terms with that, they want to refocus. The surrogacy with the Romanian home-help happens by chance. Nevertheless, the film shows that the desire for a future – symbolised by the motif of the child – is not without its problems.

We also have completely different perspectives on this subject matter: Inside the Chinese Closet by Sophia Luvarà shows a man and a woman, she is a lesbian, he’s gay, who are both forced by their families to get married. For one thing, to complete the picture because the parents can’t survive without a wedding photo; for another, because the children also constitute a kind of medical insurance and pension fund. It is absolutely impossible not to comply with this model. Nowadays, the Chinese are turning to America, recreating Christian churches, putting on white wedding dresses – all just for this wedding photo. An obsession with a Western role model even though this model hasn’t been in existence for that long. Basically, the nuclear family is an invention of early industrialisation. The characters in Inside the Chinese Closet suffer under this concept and try a thousand different tricks to remain themselves whilst, at the same time, trying to avoid disappointing their parents.

The documentary Europe, She Loves by Jan Gassmann continues this topic, right?

Yes, Gassmann chose his protagonists because they all have something in common: mummy, daddy, a little home. This test-bed of industrialisation and the social fantasy that a man and a woman need a little nest. And everything is at their disposal, from drugs to sex, from IKEA to alternative modes of living. The characters are just trying to live their lives. They are all very friendly, positive people. This is shown in a nicely laconic way, without resorting to manipulation, focussing simultaneously on these four little nests in four far-flung locations on this botched-together continent.

Goat by Andrew Neel

Another aspect of the gender question is the topic of the “sensitive male” that you have identified in 2016 and which finds a particularly strong expression in Goat.

Yes, Goat by Andrew Neel is a core film in the programme. It handles this topic very well. I take “sensitive male” to mean a man who, in his understanding of his role, departs from what the conservative model dictates. Goat shows how young men are destroyed by the initiation rites of American student fraternities in order to retain the supremacy of the USA’s white male elites. Such practices resemble those in Abu Ghraib. Empathy, pain and dignity are systematically exorcised. In this way the future elites are made fit for their careers as the bosses of banks who mercilessly rob people. Goat is produced by James Franco and he also acts in it. Christine Vachon, who is being presented with a Special Teddy in 2016, was also a producer and David Gordon Green, who won a Silver Bear in 2013 as a director, co-wrote the screenplay.

Nakom by Kelly Daniela Norris and TW Pittman

The Suddenness of Events

Another motif is the many sudden strokes of fate, accidents and killing sprees that accumulate in this year’s programme. Aquì no ha passado nada (Much Ado about Nothing), Grüße aus Fukushima (Fukushima, mon Amour), Kater (Tomcat), Remainder... to name just a few. Does this speak of a global unease that is making itself felt in this way?

That’s a good question. The incidents are not actually foreseeable. In Kater the situation is paradisiacal and then this self-created catastrophe arrives which is inexplicable.

At the same time there is a large number of films in the programme in which a character returns to the village, the family, tradition. Nakom from Ghana or El rey del Once (The Tenth Man)...

I find the motif of return highly interesting because it says something about our time and that is actually the Panorama’s aim: to present a picture of the world’s zeitgeist. And to return means a longing for the security of home; it speaks of a need for the unquestioned and warmth. However, the protagonist in Nakom by Kelly Daniela Norris and TW Pittman only stays there for a short while before he returns to his own life. He leaves tradition behind again once he has put things in order there.

In El rey del Once by Daniel Burman, a young Argentinean Jew who has been living in New York returns to Buenos Aires. He has a very different perspective on the past and the neighbourhood of Once which gives the film its title. He keeps his distance but observes his home with less hostility than at the point when he had to free himself from it.

Hotel Dallas by Livia Ungur and Sherng-Lee Huang

Of Capitalists and Socialists

We see another return in Hotel Dallas. The film shows the Romanian escape into capitalism via the images on TV and appears to be completely at odds with everything that defines the enlightened, politically correct European of today. What made you include this film in the programme?

JR Ewing, one of the main characters in the American TV series Dallas and the archetypal unscrupulous capitalist, was an unbelievably successful role model for many people who I don’t know, because I live in a parallel universe with people who actually want a better world for everyone and who are interested in art. We don’t realise that the other half of this world is full of JRs. The demise of the Ceausescu era in Romania offered the chance to create something distinct and new; instead, the inhabitants are crazy about this capitalist nonsense, like the protagonist Ilie who, following the collapse of the socialist system, recreates his own Dallas. His daughter emigrates from Romania to the USA and now returns to show Bobby, the "nice" character in Dallas, her homeland. This means she guides Patrick Duffy, who played Bobby, through this post-socialist world. The film actually makes him grapple with this world and is told with the kind of stoical irony which only really comes from the East.

Before Stonewall by Greta Schiller and Robert Rosenberg

One final question: the plot from The Lovers and the Despot by Rob Cannan and Ross Adam sounds like it comes from the most overactive imagination and yet it’s a documentary, isn’t it?

An incredible story. The North Korean president Kim Jong-il arranges for the dream couple of the 1950s South Korean film industry to be kidnapped by his secret services because he’s obsessed with film and wants to give a helping hand to his country’s film industry. The Lovers and the Despot contains a great deal of original material: Jong-il with his rockabilly hairstyle... The conversations with him were recorded on tiny dictaphone tapes and you can hear all that in the film. Even if the material had been faked, it would still be a great film!