2018

68th Berlin International Film Festival

February 15 – 25, 2018

Best of Berlinale 2018

“The magic of the Berlinale derives from the audience itself. For everyone present, it is as simple as it is complicated: a journey into one’s own emotions, a short trip out of the bustling city into the world of possibilities to live one’s life in a different way.” – Robert Ide, Der Tagesspiegel, February 26 2018

In one sense, the 2018 Berlinale began early: on November 24, 2017. With the somewhat sensationalist title “Filmmakers Want to Revolutionise the Berlinale”, Spiegel Online published an appeal from 79 film directors that the procedure chosen to select the new Festival Director should be transparent. This was a legitimate request. Dieter Kosslick’s contract ended in 2019 and the processes of appointing leading positions in Berlin’s cultural institutions had in recent years sometimes lead to unfortunate choices and even met with massive opposition – the memory of the turmoil following the installation of Chris Dercon as artistic director of the Volksbühne was still fresh.

But what then turned the appeal into a farce was the article in which the few words from the filmmakers were embedded. Hannah Pilarczyk wrote: “Instead of sharpening the profile of the festival in terms of content, Kosslick has sought to counter the loss of significance with a constant expansion of sections and special presentations. This has led to a mess of programmes which in themselves are as insubstantial as the competition and mean that attention and discussion is scattered rather than concentrated” (Spiegel Online, November 24, 2017). Instead of focusing on the deficiencies and structures of cultural policy, the debate was turned into a final reckoning of the Festival Director. This was a totally unintended turn of events, as one of the joint signatories, Christian Petzold, later made clear: “Our appeal became personalised and was turned into a judgement of Dieter Kosslick, even though he had nothing at all to do with it” (in an interview with Der Tagesspiegel, February 16, 2018). An incensed Dominik Graf similarly spoke out: “If I had known that our letter would be dragged into the journalistic swamp of a judgement on Kosslick, I would never have signed it” (in Die Zeit, November 29, 2017).

The appeal was instrumentalised to channel often personal and long-held sensitivities into a kind of vendetta. In the Spiegel article, Pilarczyk basically did nothing more than bring into play the unease at an increasing “gigantism of the festival” (Yearbook 1988)) that has been simmering amongst Berlinale critics for 30 years to insinuate that the signatories wanted to “deliver a damning indictment of the Kosslick era”. The man himself could only react laconically to the persistent hostility: “Well, it’s quite baffling, really [...]. It was initially [...] aimed at the process but then it attacked me [...]. I have long been hoping for specific proposals about what we should do. But apart from the suggestion that we should make the Berlinale smaller, nothing has been forthcoming so far” (in an interview with Deutschlandfunk Kultur, February 15, 2018).

The festival and the city - Berlin, February 16, 2018

The Diversity of the Film/World

To make the Berlinale smaller, the call for a stronger curatorial hand – demands that have become as intrinsic to the festival as the cold weather. In light of the journalistic mudslinging in the run-up to the 2018 Berlinale, the impression might have arisen that Dieter Kosslick would be handing over a desolate and meaningless event to his successor in 2019. That this was not the case was proven by the festival itself, its programme and the journalistic debate arising in its wake. It became clear that the Berlinale is alive and kicking: its uniqueness clearly stood out in 2018.

Rather than exposing an untenable situation requiring urgent revolution, critics like Hannah Pilarczyk simply held an opinion which differed from others. And it was an opinion, as things turned out, that was not shared by the majority. “The tangled undergrowth, the profusion – that is the urban jungle, that is Berlin. It is what differentiates the Berlinale from the hysterical clarity of the small towns of Cannes and Venice [...]. The critics [...] fail to grasp the Berlinale because they have already failed to grasp Berlin. One should not accommodate them by pruning this film festival into something that complies with an authoritarian small-town character and its fantasies of control,” wrote Jens Jessen in Zeit Online on February 14, 2018. You only needed to take an early morning stroll across Potsdamer Platz and observe the slowly awakening bustle of journalists, industry visitors, audiences, selfie hunters and tourists to comprehend the special quality and atmosphere of the festival.

It was never a goal of the festival to court hermetically sealed specialist discourses. At its centre stood diversity and an enthusiastic audience who packed the cinemas once again in 2018. “Does it not demonstrate cinephile self-aggrandisement to believe that the audience requires a strong guiding hand? Instead, one should have the confidence that, in this complex world, people are able to navigate their way through a substantial programme brochure and allow it to inspire them,” argued Wenke Husmann in Zeit Online (February 15, 2018).

A bath in the crowd: Joaquin Phoenix at the premiere of Don’t Worrry, He Won’t Get Far on Foot

Her plea for diversity found prominent support: “I usually hate film festivals. Last night, Gus [Van Sant] was doing the Berlin Talents and I went along to watch and saw all these young filmmakers that are curious about the process and hearing Gus speak, I had a real appreciation for a film festival,” said Joaquin Phoenix, in Berlin for the premiere of Gus Van Sant’s Don’t Worrry, He Won’t Get Far on Foot, about his first positive festival experience (deadline, February 21, 2018).

As in previous years, the days of the festival celebrated the opportunity provided by almost 400 films to travel round the world, experience the most diverse milieus, ways of life, opinions and attitudes, and to put one’s own preconceptions and prejudices to the test. “The eyes of many Berlinale viewers are shining when the credits roll and they ponder the films in the Panorama, Forum or Generation sections on which they have fruitfully lavished their time in recalibrating their own world view,” wrote Robert Ide (Der Tagespiegel, February 26, 2018). The 2018 Competition was representative of the immense diversity of the entire festival. Film critic Katja Nicodemus admitted: “I have never experienced anything like it, so many different aesthetics and crazy film ideas” (NDR Online, February 22, 2018).

For the very first time in its history, the Berlinale opened with an animated film: Wes Anderson’s Isle of Dogs was not only a curatorial stroke of luck, bringing the necessary star power to the festival’s first Red Carpet, but also a “parable of a world filled with fascist ideas of purity and exclusion” (Verena Lueken, FAZ, February 16, 2018) and hence a paradigm for the festival’s concept of diversity.

At the premiere of Bixa Travesty (Tranny Fag): director Kiko Goifman, Panorama section head Paz Lázaro, director Claudia Priscilla and protagonist Linn da Quebrada

#MeToo and Diversity

In mid-October 2017, the MeToo hashtag dominated social networks. It was established in the wake of the heated debates on gender relations in the film industry triggered by the scandal surrounding producer Harvey Weinstein. Several female actors have accused Weinstein of sexual assault, up to and including rape. The issue had wide repercussions, including in Germany, and became a dominant topic at the 2018 Berlinale where Dieter Kosslick put #MeToo in a wider context and focused on power relations in general. Such discussions are “also a bit in the DNA of the Berlinale” (in an interview with Deutschlandfunk Kultur, February 15, 2018) because this issue, too, is ultimately about diversity. The festival’s commitment was accordingly recognised by the press: “Where else can cinema-goers find such a wide range of queer, international and political movies without working as an industry insider? Certainly not Cannes nor Venice, both of which remain privy only to those with the correct pass […]. Much like Berlin itself, the Berlinale prizes inclusivity above all else, and in this tumultuous era, it’s hard to imagine anything more important than that” (David Opie, EXBERLINER, 09 February 2018).

The last days of eastern Aleppo’s siege: : Milad Amin's Ard al mahshar (Land of Doom) from Forum Expanded

The Obstructed View

With #MeToo, the film world turned its attention to its own structures, and in view of the current global political situation, the 2018 festival also became a question of identity. The image of a world out of joint already present in previous years had only sharpened and the Berlinale, which began in 1951 as a “showcase of the free world”, had to ask itself whether this free world even still existed. The so-called “leader of the free world”, a buffoonish US billionaire now unexpectedly a year into office, had still not forsaken his fantasy of a concrete wall between the USA and Mexico, had introduced protective tariffs, fired his foreign minister by Twitter and was himself accused of sexual assault. A continuing manifestation of this chaos was bomb-flattened Syria. The (proxy) wars between Russia and the USA, the interests of Turkey, the Kurds, Bashar al-Assad, the dystopian ideals of Islamic State, etcetera, were being fought on the backs of a fleeing or dying civilian population. Most of the world closed its eyes to the mass murder taking place.

It was therefore all the more important that a trend from previous years continued in the 2018 programme: films again challenged the act of forgetting and insisted on holding the past to account, and this took place across all sections. As Christoph Terhechte, head of Forum, summarised in an interview: “Addressing the past is what preoccupies filmmakers most at the moment. Especially because the view of the future is so obstructed worldwide. It is very hard to imagine what our civilisation will look like in 20 or 50 years time. To find answers to this question requires taking recourse to the past because it contains the reasons for the current situation. That is the prerequisite for future utopias.”

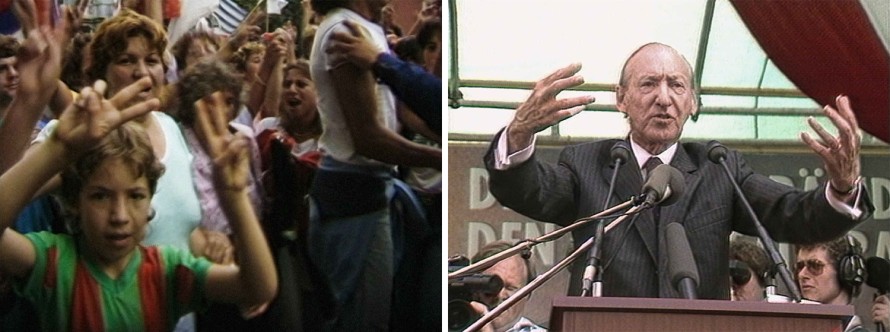

Two films, both using material originally shot in the 1980s: Unas preguntas (One or Two Questions) by Kristina Konrad and Waldheims Walzer (The Waldheim Waltz) by Ruth Beckermann

Nationalism Then as Now

It was striking how frequently the focus was trained on the devastation caused by dictatorial regimes. In his Competition entry Ang Panahon ng Halimaw (Season of the Devil), Lav Diaz returned to the darkest hours of the Marcos regime in the Philippines. Almudena Carracedo and Robert Bahar’s The Silence of Others in Panorama depicted the fight against the state-sanctioned forgetting of the Franco regime in Spain. An amnesty law issued after the military dictatorship in Uruguay was at the centre of Unas Preguntas (One or Two Questions) by Kristina Konrad in Forum. Konrad drew on material she shot in the 1980s to show how active democracy worked then and should work today. In a similar way, Ruth Beckermann edited together footage she also shot in the 1980s. In Waldheims Walzer (The Waldheim Waltz) she followed the – successful – 1986 election campaign of former UN Ambassador Kurt Waldheim as he ran for the office of Austrian Federal President. At that time, Waldheim had consigned his Nazi past to oblivion and thus became a symbol for an entire nation which perceived itself as a victim of the Nazi regime rather than its accomplice. Waldheims Walzer insisted, and persisted, in scrutinising and refusing to forget – and for this the film was rewarded with the Glashütte Original – Documentary Award. Beckermann’s film also had a burning topicality as the shift to the right and the resurgence of nation states was in evidence everywhere in our supposedly globalised world.

That certain milieus or individuals have long since bid farewell to the idea of democracy was reflected in multifaceted ways in the 2018 programme. In Až přijde válka (When the War Comes) in Panorama, Jan Gebert documented the preparations made by a paramilitary group in Slovakia for the self-heralded clash of civilisations. The most shocking aspect of this was the commonplace way in which paramilitary posturing was integrated into people’s everyday lives. The catastrophe to which such ways of thinking can lead was made tangible by Erik Poppe in the Competition. With Utøya 22. juli (U – July 22) he delivered the audience back to the year 2011 and the warzone of a war without borders, to the mass murder committed by the self-proclaimed defender of the Western world Anders Breivik who, unwilling to wait any longer for the clash of civilisations to begin, transformed the Social Democrat Party’s youth camp into the scene of a massacre.

War games: Až přijde válka (When the War Comes) by Jan Gebert

Revolution of the Senses

Beyond its topic, Utøya 22. juli also impressively tackled the prerequisite of any form of politics: perception. With a running time of 90 minutes, the film’s length corresponded to that of the 2011 massacre itself. Poppe eschewed cuts and hence the audience experienced the flight and dying of the Norwegian teenagers in an, at times, agonising tour-de-force of a single take. Allowing the events to play out in real time made the suffering and fear tangible in a much stronger way than any conventional documentary could hope to achieve. Just how strongly form is connected to political implications was also demonstrated by Nesrine Khodr’s installation Extended Sea in the Forum Expanded exhibition. Here, once again, a single, and in this case, fixed shot: for 705 minutes almost nothing happens. Anyone who could spare over eleven hours – and particularly in the context of a film festival where the limited nature of time and the imperative to accumulate the greatest possible number of viewed films dictate the daily schedule – to devote their full attention to a single work has obviously left behind the premises of turbo-capitalism and can also perceive the social world in an entirely new way.

Extended Sea by Nesrine Khodr

Extended Sea found its counterpart in Panorama where Profile offered a wonderful reflection on the state of perception in the digital age. Timur Bekmambetov told the story of a British journalist who allows herself to be recruited by IS via Skype in order to write an article about it. For him, a mere laptop screen was sufficient cinematic space, where the ways in which perception becomes hysterical and incredibly accelerated can be experienced, as can the abstruse manner in which the private and professional, life and death, are pieced together in hard cuts. “From the point of view of a normal resident of audiovisual culture, film festivals are only as good as they are representatives, engines and reflections of general image culture” wrote Georg Seeßlen in Freitag (07/2018 edition) – and the 2018 programme had no reason to shy away from this demand.

A Farewell and Three Welcomes

In the summer of 2017, Panorama saw a significant change in personnel. After 25 years, Wieland Speck passed the leadership baton to Paz Lázaro who curated the programme for the 68th Berlinale together with Michael Stütz and Andreas Struck. All three had worked for Panorama for a long time already and they continued to focus on key topics such as LGBT cinema. At the same time, their very own distinctive styles became clearly visible in a focused and compact programme.

And it was also an end of an era at the European Film Market: after 30 years the grande dame of the film world, Beki Probst, was bid farewell with a Berlinale Camera. As director and then president, she had made the market an incomparable success story. “I began with three colleagues and a handful of films,” she recalled in the Tagesanzeiger (February 15, 2018). In 2018, with 10,000 participants from 112 countries and 661 films screened, the EFM set new records.

At the Award Ceremony: The team of Touch Me Not with the Golden Bear

“Sexperiments”

The 2018 festival reserved its biggest surprise for the Award Ceremony. Instead of awarding one of the tipped favourites in the Competition, Jury President Tom Tykwer and his fellow jurors honoured a “small”, semi-documentary film experience from Romania which hardly anyone had on their radar: Touch Me Not by Adina Pintilie took home both the GWFF Best First Feature Award and the Golden Bear. Its candid treatment of naked bodies, sexuality and intimacy had already caused a stir at its premiere two days earlier. Some critics left the screening in a huff, lurid headlines blazed for the next few days: “Gold for the Nude Shocker” (Berliner Morgenpost), “Sexperimental Film ‘Touch Me Not’ Unsettles Berlinale Audiences” (Rolling Stone), “Audience Members Walk Out Due to Excessive Sex Scenes” (Die Welt).

In a time of an omnipresent digital porn economy, Pintilie had struck a nerve. The film investigates the fundamentals of what is termed “intimacy”, what defines it and how it is experienced. In view of the heterogeneous bodies and personalities it portrays - Pintilie’s protagonists are all psychologically or physically peculiar in their own way – rather than the nudity in the film, it is the normativity of the “beautiful” bodies which generally prevail on our cinema screens which seems monstrous. Pintilie’s film discovers beauty in what is all too often excluded and marginalised and in the #MeToo era it was another powerfully urgent plea for true diversity. Reactions to the Golden Bear winner were heated and divergent. Peter Bradshaw from the Guardian took the jury’s decision as an opportunity to make a personal reckoning of the festival as a whole: “Victory for Adina Pintilie’s humourless and clumsy documentary essay underscores Berlin’s status as a festival that promotes the dull and valueless” (February 25, 2018). Tobias Kniebe, in contrast, wrote in the Süddeutsche Zeitung: “And a film that succeeds in completely rewiring a few synapses in the brains of its viewers – does that not deserve all the Bears going?” (February 25, 2018).

Alonso Ruizpalacios and Manuel Alcalá celebrating the Silver Bear for Best Screenplay

The passion of the debate unleashed by Touch Me Not also demonstrated the exceptional quality in the 2018 Competition in which many films deserved a prize. Above all, the German critics were disappointed that the four strong German entries – Christian Petzold’s Transit, Emily Atef’s 3 Tage in Quiberon (3 Days in Quiberon), Philip Gröning’s Mein Bruder heißt Robert und ist ein Idiot (My Brother’s Name is Robert and He is an Idiot) and Thomas Stuber’s In den Gängen (In the Aisles) – went home empty-handed. Gunnar Decker succinctly summed up the general mood in Neues Deutschland on February 26, 2018: “This year’s competition [was] one of the strongest in recent years. Above all, it saw a return of strong German films which surprised with very different distinctive styles.”

The other awards revealed how multifaceted and diverse the 2018 Competition was: Małgorzata Szumowska won the Grand Jury Prize with her satire on contemporary Poland, Twarz (Mug); Wes Anderson secured consideration for his animated film Isle of Dogs with the award for Best Director. The quiet, intimate Paraguayan drama Las herederas (The Heiresses) by Marcelo Martinessi won the Silver Bear Alfred Bauer Prize and the Silver Bear for Best Actress for Ana Brun.

Anthony Bajon with the Silver Bear for Best Actor

For his role as the drug-addicted young drifter in Cédric Kahn’s La prière (The Prayer), young French performer Anthony Bajon won the Silver Bear for Best Actor. The prize for Best Screenplay went to Mexico for Manuel Alcalá and Alonso Ruizpalacios’ (who also directed the film Museo (Museum)) retelling of the audacious 1985 break-in at the Mexican National Museum. The Russian Elena Okopnaya was honoured for her Outstanding Artistic Contribution (Costume and Production Design) in Alexey German Jr.’s portrait of the artist Dovlatov.

And so the 68th Berlinale climaxed in an Award Ceremony which once again reflected the great diversity of the festival. As Hanns-Georg Rodek summed up: “The Berlin Film Festival is returning to its roots. It’s once again a political festival of free thinking that ventures to take more risks than Venice or Cannes. ‘Touch Me Not’ is a signal to the other festivals that this Berlinale is ready to change. And a signal to all filmmakers that they are looking to take risks” (Die Welt, February 25, 2018). Amongst the critics, anticipation for next year and the 69th Berlinale won out in the end. Tim Caspar Böhme, for example, wrote: “This year could [...] turn out to be the prelude for an increased understanding of the Berlinale as an experimental laboratory for films. Which would be no bad thing” (Die Tageszeitung, February 25, 2018). The alleged sense of deep crisis proclaimed by Der Spiegel in late November had, by the end of February, ultimately been transformed into a hopeful spirit of optimism.

Facts & Figures of the Berlinale 2018

| Visitors | |

|---|---|

| Total amount of theater visits | 489,791 |

| Tickets sold | 332,403 |

| Professionals | |

| Accredited guests (press excl.) | 18,080 |

| Countries of origin | 130 |

| Press | |

| Journalists | 3,688 |

| Countries of origin | 84 |

| Screenings | |

| Number of films in the public programme | 380 |

| Total amount of screenings | 1,096 |

| European Film Market | |

| Film industry participants | 9,973 |

| Number of films | 780 |

| Number of screenings | 1,112 |

| EFM-Stands (Martin-Gropius-Bau & Business Offices) |

201 |

| Number of exhibitors | 546 |

| Berlinale Co-Production Market | |

| Participants | 579 |

| Countries of origin | 54 |

| Berlinale Talents | |

| Participants | 251 |

| Countries of origin | 79 |

| Annual budget | € 25 million |

| The Berlin International Film Festival receives € 7.7 million in institutional funding from the Federal Government Commissioner for Culture and the Media. |